Restorations at Stonehenge

WRITTEN BY Austin Kinsley ON 10/01/17. Restorations at Stonehenge POSTED IN Stonehenge

The modern story of restorations at Stonehenge begins in 1880 when the site was surveyed by William Flinders-Petrie, who also established the numbering system for the stones that is in use to this day. The very first documented intervention to prevent stone collapse at Stonehenge happened in 1881 and is described here by Simon Banton. In 1893, the Inspector of Ancient Monuments determined that several stones were in in danger of falling and he was subsequently proved correct when stone 22 collapsed in a New Year’s Eve storm on 31 December 1900. The stone remained intact and was not damaged, but lintel-122 broke into two pieces with such a shock that a fragment was found 81 ft away. They were the first stones to fall since 1797 (after a rapid thaw succeeded a hard frost) and, as the guardian of the site was ill at the time, Sir Edmund Antrobus paid for a police constable to keep sightseers in order.

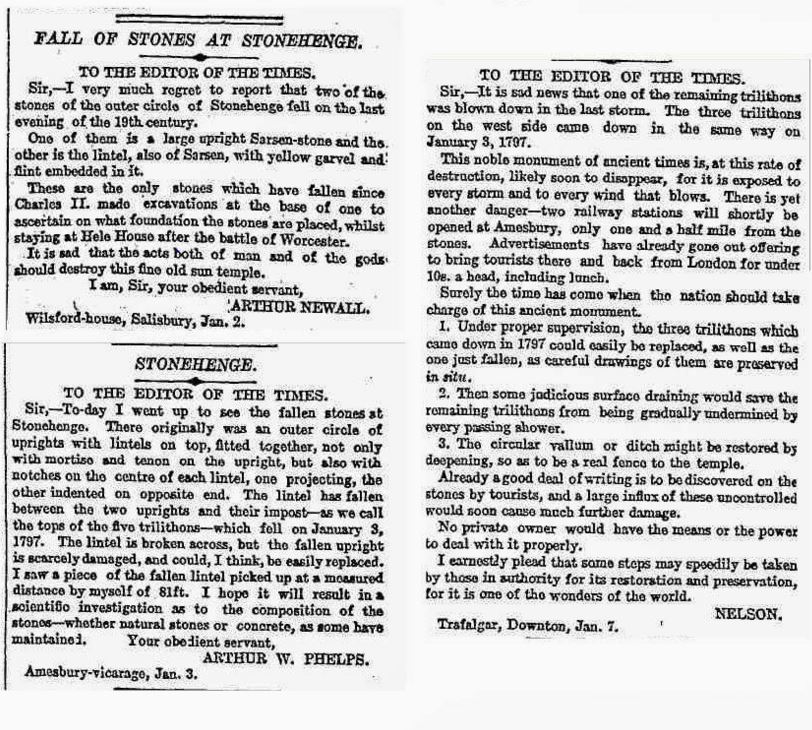

A number of letters were written to the Times newspaper as a result of the fall of the stones on that portentous last evening of the 19th century.

A meeting was held at Stonehenge with Sir Edmund Antrobus the owner of the monument in March 1901 (reported in the Times newspaper on 13 April 1901) to discuss the question of the best and wisest steps to be taken to ensure the safe-keeping and future preservation of the monument. The advice given by the representatives of the Society of Antiquaries, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Monuments and the Wiltshire Archaeological society was:

- To fence the circle in, enclosing as large an area as possible, so as not to interfere with the general view of Stonehenge.

- To make safe specific stones (of the outer circle, etc) in danger of falling under certain conditions of frost, storm etc.

- To set up in their old places, which are accurately known, the two stones which fell on December 31st, the last day of the old century during the terrific gale with which the new century was ushered in.

Observations with a theodolite were made on June 25 of the position of the rising sun by Mr. Howard Payn of the Solar Physics Laboratory, S. Kensington.

Lady Antrobus observed the restorations at Stonehenge carried out in September 1901, resulting in an article she authored being published in the Saturday October 19th, 1901 edition of Country Life, in which she observed:

‘The most dangerous and intricate piece of work to be undertaken was the raising to an upright position of the great monolith called the Leaning Stone, the king of the mystic circle and the largest in England, Cleopatra’s needle excepted. This stone was one of the uprights of the great trilithon which stood behind the Altar Stone, and the Duke of Buckingham is said to have caused its fall by his digging and researches in 1620. The fallen upright is broken in two pieces and its lintel lies, as it fell, across the Altar stone.’

Below: Two photographs by Lady Antrobus of the great trilithon stone 56 before it was straightened in 1901. The upper image shows it leaning hard over onto bluestone 68, which can be seen here in the foreground to the right.

‘The supervision of the work raising the great monolith was entrusted to Mr. Detmar Blow, architect. Dr. Gowland, Professor of Mineralogy at the Royal College of Science, took charge of the excavations, and Mr. Carruthers advised upon engineering questions.’

Excavations were made both in front of and behind the leaning stone 56 and its fallen and broken partner stone 55. A Roman coin (a sestertius of Antonia) and a George III penny were found (at a shallow depth), and many chippings of both the blue and the sarsen stones. Numerous flint axe-heads and large stone hammers (weighing from 37 to 64lbs) were also found at a depth of from 2 feet to 3 feet, 6 inches. A pick of deer antler was found close to the bottom of one of the holes. Interestingly, a stain of bright green (the colour of corroded bronze) marked a sarsen block seven feet down. Lady Antrobus also observed that animal bones had been found.

Below: Sarsen mauls and flint hammerstones excavated during the restorations.

Stone 56 is just short of 30ft long and more than 8 ft of it was embedded in the ground, originally holding the lintel 21 feet above the ground. Its partner, stone 55, was only 25 feet long and had to be held in place with a little over 4 feet of its base set in chalk.

Lady Antrobus continues:

‘The great work was started in August (1901) and finished on September 25th, having taken six weeks to complete … Large excavations were made round the base of the stone, and filled with concrete, which hardening was to hold it fast. The base of the stone was found to be at a depth of 8 feet 6 inches in the ground and the surface worked with flint tools. It was beautifully set, showing great knowledge on the part of the builders … There are further questions of the raising of the two stones which fell last year, the original positions of which are accurately known, also of certain precautionary measures to be taken to prevent the falling of other stones which are in danger. I think it would be in the worst possible taste to restore Stonehenge in any sense, but I can not agree with those who say ‘Let the stones lie as they fall and take no precautionary measures.’

I consider this to be a false argument, as Stonehenge, if left severely alone, would soon present the appearance of a jumbled heap of ninepins, many of the stones having reached a condition when they are liable to be blown down by any gale from the west, such as the one experienced last year.

After Stonehenge was subsequently sold at auction on 21 September 1915 here as a direct result of the tragedy of the first world war which devastated the Antrobus family here, it was bequeathed to the nation in 1918 and the Office of Works subsequently became responsible for the upkeep of the monument.

Lt. Col. William Hawley excavated at Stonehenge between 1920 and 1927. He righted six stones, enabling the removal of the unsightly larch poles which had previously been supporting them. He set these stones in concrete beds after excavating the sockets.

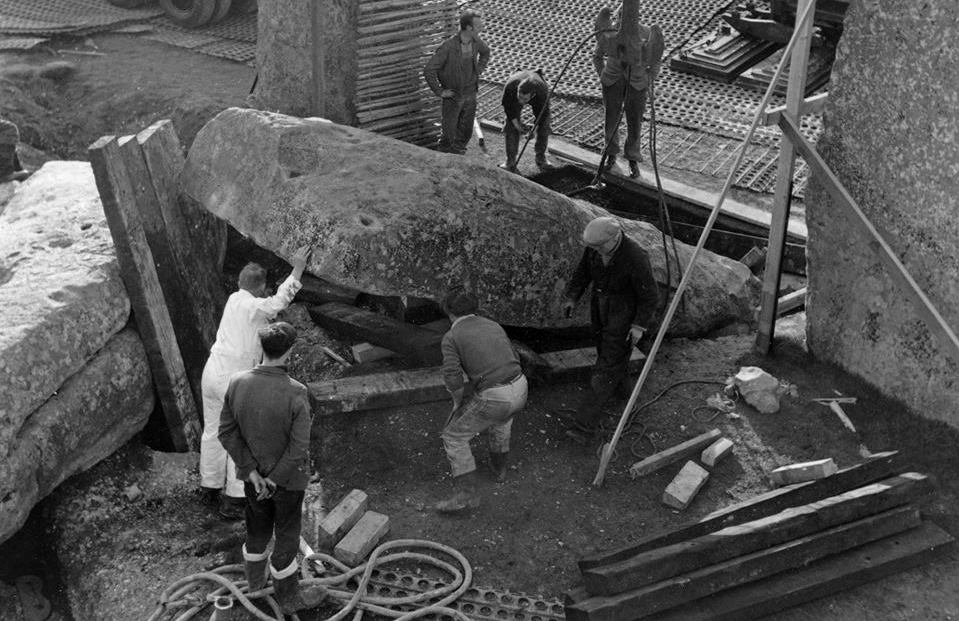

In 1950 Professor Richard Atkinson and other archaeologists began a thirteen year period of excavations and restoration work at Stonehenge. A decision was made to restore the stones that fell in 1797 and 1900, at a planned cost of £8500. In 1958 the work of lifting the west trilithon began. Two cranes were utilised, including a huge Bristol Barabazon aircraft crane, loaned by the RAF at nearby Boscombe Down.

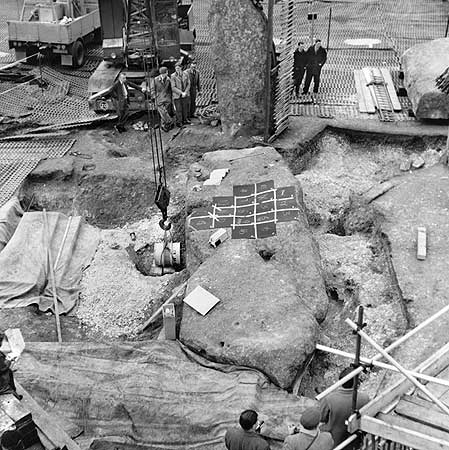

Below: The fallen west trilithon stone 58 in the central foreground with stone 57 behind and to the right their lintel 158 before re-erection. The two bluestones 69 and 70, in the foreground to the left here, were removed, replaced and straightened in 1958.

In his book ‘ Stonehenge‘, Professor Atkinson writes:

‘The stone holes of the fallen trilithon (stones 57 and 58) were both found to be very shallow. Indeed it is remarkable that these two stones had not fallen long before 1797, so insecurely they were rooted in the ground. This shallow depth doubtless accounts for the absence of any well-defined ramp leading down to the holes. In both cases, however, it was clear that the stones had been raised from the outside, that is from the northwest, or indeed approximately from the positions in which they lay after they fell. In both holes, on the inner side, were traces of decayed anti-friction stakes which had served to protect the back of the hole from being crushed by the toe of the stone, as it was being raised.’

Interestingly, in the next paragraph Professor Atkinson adds some additional observations in respect of the original erection of stone 56, which had been straightened by Professor Gowland and his team in 1901:

‘To the west of the fallen trilithon, and partly buried beneath the fallen stone 57, we found an immense sloping ramp, cut in the chalk and filled with tightly packed chalk rubble, running inwards and downwards directly towards the base of stone 56, the surviving upright of the central trilithon.There can be no doubt that this ramp was used in the erection of stone 56. And for this purpose a ramp would indeed be very necessary, since the bottom of the stone hole lies about 8 ft below the present ground surface, far deeper than in the case of any of the other sarsen stones of which we have details. The position of this ramp makes it clear that stone 56 was either put up sideways, lying initially on its narrower western edge; or else, if it originally lay flat on its broad face, must have been turned through ninety degrees after it was upright. Either of these proceedings must have been more than ordinarily hazardous, and we can only assume that there was some very compelling reason for departing from more straight forward methods of erection.’

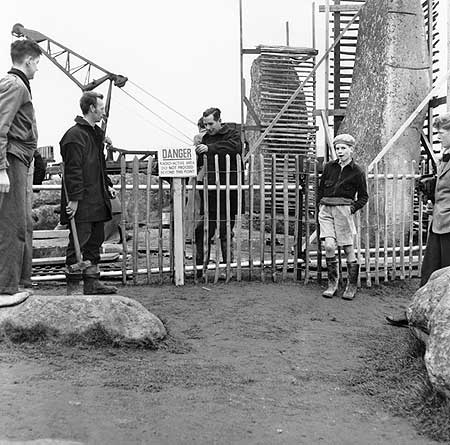

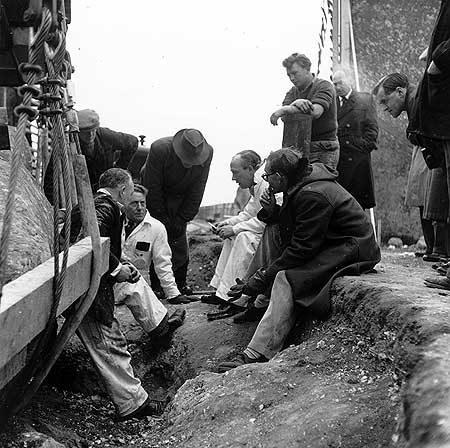

Below: These three photographs were taken in May 1958. Concerns were raised that a bedding plane shear may destroy stone 58 as it was lifted, as a result of which the X-ray machine, which can be seen being lowered here, was used to examine it. Subsequently, ‘three cores were drilled, bolts inserted to ensure the two layers of the stone held together and the bolts hidden by the replacement of the ends of the cores into the holes’. An area was fenced-off while radio-active material was used to assess cracking in fallen stones.

Below: Lifting Bluestone 36 with block and tackle.

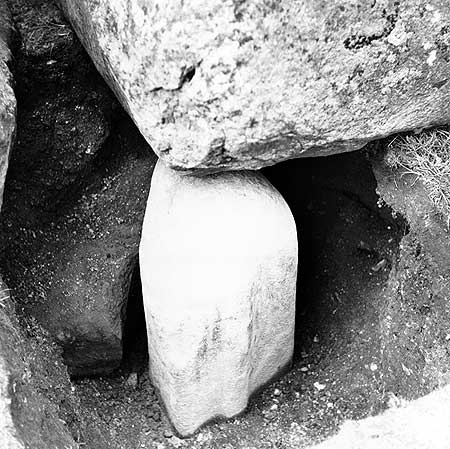

Below: ‘Bluestone 36 as excavated in 1953. Notice the two mortises and fine craftsmanship. It was used as a lintel long before it ended up as a circle stander. It was returned to the hole after being examined.’- Neil Wiseman, Stonehenge and the Neolithic Cosmos here.

More on the current position of bluestone 36 at Stonehenge here.

Below: ‘Lintel 158 is hoisted into position on top of the restored west trilithon.

More on the sarsen lintel stone 158 here.

Neil Wiseman in Stonehenge and the Neolithic Cosmos writes, ‘A large concrete vault was formed in the ground and each of the trilithon uprights were lowered into prepared slots, positioned precisely as they had been originally. Along with crowds of onlookers, newsreel and still cameras recorded Lintel 158 being lifted, lowered and shimmed snugly back onto the stack.’

Below: ‘Lintel 158 is hoisted onto its perch atop the restored west trilithon. The borrowed RAF ‘Babarazon aircraft crane could lift up to 60 tons — approaching its limits with the huge stone uprights.’

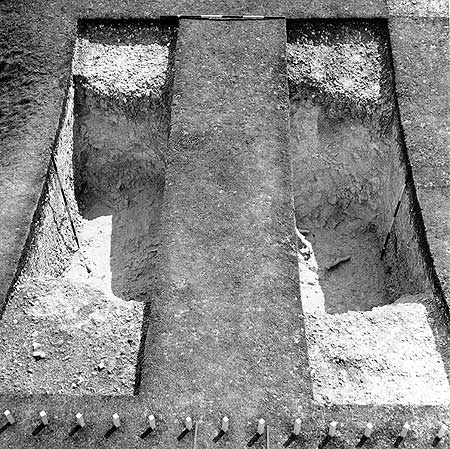

Below: During the spring of 1958 the whole area was screened down with timbers in a herringbone fashion to the chalk, to prevent the heavy machinery damaging the fragile ground surface. With the west trilithon stones to be re-erected having previously been lifted aside, a broad swath of ground is clearly visible in this photograph.

Below: ‘Mr T. A. Bailey, senior engineer, examining the lintels over stones 19, 20 and 1 of the outer circle. These stones were not moved by (Professor) Atkinson but had been straightened by Professor Hawley in 1920. These stones mark the entrance to Stonehenge.’- Historic England. The archaeologist Stuart Piggott can also be seen in the photograph, on his knees smoking a pipe.

Below: Bluestone 66, excavated in 1953. This spotted dolerite bluestone 66 is now a ground-level stump underneath the southern corner of fallen Stone 55b and can be seen here. The tongue on the face of the stone can be seen in this photograph.

Below: Post holes revealed.

Below: Periglacial stripes of the upper Avenue looking east. These gullies created by ice or meltwater may have played a part in the original decision to position Stonehenge at this location.

Below: ‘Cuttings C41 and C42 across Segment 98 of the henge ditch. Two antlers found at the bottom of C42 (seen in this image) gave calibrated radiocarbon dates of 3340-2910 cal BC.’ – Historic England.

Below: Looking northwest.

Below: A site meeting, Professor Atkinson is in the foreground here, seated to the right.

Below: ‘Bluestone 69 of the the Bluestone Horseshoe being temporarily removed during work to re-erect trilithon stones 57 and 58.’ – Historic England.

Below: ‘Stone 23 of the outer sarsen circle, which collapsed in December 1900, being lifted prior to its re-erection.’ – Historic England

Below : Bluestone 69 being removed to allow a crane access to lift fallen trilithon stones 57 and 58.

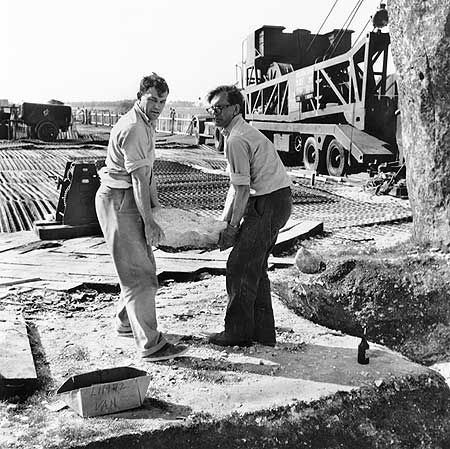

Below: Moving stone 22.

In Neil Wiseman’s Stonehenge and the Neolithic Cosmos, he writes Stone 22 was re-erected and lintel 122, cleverly repaired with steel rods, was slung back into place on top of stone 21 and stone 22.

The repair to lintel 122 can be clearly seen in photographs here on The Stones of Stonehenge website.

Professor Atkinson writes, ‘When the broken lintel belonging to these two stones (stone 21 and stone 22) was being repaired, two sets of mortices were found on its under surface. The deeper and wider pair were set symmetrically at equal distances from the ends of the lintel. The shallower pair on the other hand, though separated by the same distance from each other, were offset by about twelve inches towards stone 21, so that at this end the mortice was very close to the end of the lintel.

From these observations we may conclude that the mortices in this lintel (and very probably in all the lintels) were prefabricated while the lintel was still on the ground, and that the corresponding tenons on the adjacent uprights were them worked at the correct distance apart. In this instance, however, the accidental breaking away of part of the top of stone 21 increased the span to be bridged between this stone and stone 22, and also drastically reduced the bearing surface on stone 21, on which the two ends of the lintels had still to be supported.

Under the changed circumstances resulting from this accident, it was impossible to set the lintel in the position originally intended. Instead, it had to be moved about a foot anti clockwise; and this meant that the original pair of mortices could no longer be used, so that a new pair had to be made.’

Below: The top of sarsen stone 23, showing two tenons to secure lintels. The stone collapsed in 1964 and was re-erected by Professor Atkinson in 1964. Encased here in a protective cradle, ready for re-erection.

Below: Moving stone 22.

In his book ‘ Stonehenge‘, Professor Atkinson writes:

‘In the outer circle of sarsens the stone hole of stone 22 was also examined before the stone was re erected in it. Here too there was clear evidence that the stone had been erected from the outside. But when the adjoining stone 21 was investigated, as a preliminary to straightening it, the back of the hole, set with anti friction stakes, was found to be on the outer side of the circle, and the ramp correspondingly on the inner side. This is the only stone which is so far known to have been raised from within the circle, and the reason for this departure from the usual method is not at all clear.’

Below: ‘Professor Richard Atkinson and another archaeologist remove one of the stones used as packing for the uprights of the outer sarsen circle.’ – Historic England

Below: Mr T. A. Bailey, Senior Engineer, measuring the inclination of stone 54.

Below: Checking stone 56.

Below: Y hole 16 and Z hole 16.

The last restorations carried out were in 1964, when the newly fallen stone 23 was reset and stones 4 and 5 were straightened. (In the only serious incident during the earlier restoration work, stone 23 had been hit with force when stone 22 moved in its cradle.) The south trilithon was also encased in a heavy steel frame and slowly cabled upright. Since that time, other than a few cosmetic upgrades, the site has remained largely untouched. Only seven of the sarsen uprights now remain in their original chalk cut sockets.

Thank you to the Cornelius Reid family, Neil Wiseman, Simon Banton for The Stones of Stonehenge website and Historic England, for providing material used in this article. Thank you as well to Professor Richard Atkinson, who took the majority of the photographs used here and had the foresight to leave a legacy of over 2000 photographs from his 13 year span of research and restorations onsite at Stonehenge. A number of his images can be viewed here.

A detailed summary of the restorations carried out at Stonehenge between 1881 and 1939 published by English Heritage is available to read here.