5000 Year Old Lost Map of Stonehenge?

WRITTEN BY Austin Kinsley ON 26/05/14. 5000 Year Old Lost Map of Stonehenge? POSTED IN Stonehenge Incised Chalk Plaques

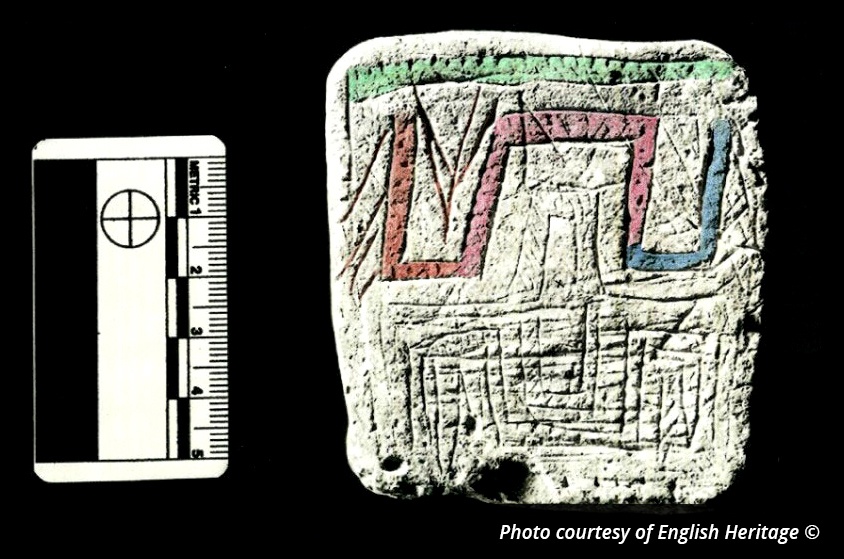

Could the above chalk plaque currently on permanent display in the Stonehenge Visitor Centre be a 5000 year old lost map of Stonehenge and its surrounding area?

I am minded this week that, other than a number of the actual stones at stonehenge, little of the dating of man’s activities in the area is similarly ‘set in concrete‘ and frequently resembles more closely the shifting sands Jacquetta Hawkes alluded to with her now famous quote ‘every age has the Stonehenge it deserves or desires’. For example, archaeological evidence indicates that the main period of construction and activity at Durrington Walls falls between 2600BC and 2400BC. Beneath the outer bank at Durrington Walls, traces of an early Neolithic settlement were found, including sherds of round-based bowls, leaf-shaped arrowheads and other flint artifacts. Excavators concluded this activity had occurred 500 years earlier than the building of the enclosure bank and is indicative that man was active in this area in 3100BC, as well as the 2600BC to 2400BC main period of activity.

The Avenue is currently generally accepted as dating from 2600BC to 1700BC. It may have evolved over a long period of time from a pathway or pathways arising from our ancestors’ movements linking the cradle of Stonehenge area in the lee of Vespasian’s Camp to activities west and northwest on Salisbury Plain itself.

A much overlooked feature to the west of Stonehenge itself is a wooden palisade running approximately southwest to northeast. In 2008 during the SRP, Mr. Parker Pearson and his team dug a number of trenches to investigate this feature. He provides a brief summary of the findings on pages 233 to 238 of the 2012 edition of his book Stonehenge and concludes ‘In terms of Neolithic remains…the results were disappointing. The palisade ditch had been cleaned out and reused in the middle Bronze Age as a boundary that formed part of a Bronze Age farming landscape of fields. We couldn’t find anything to date the palisade ditch but the fact that its line was continued by the Bronze Age ditch makes it pretty likely that it’s only a bit earlier. There was no trace of any Neolithic activity, so the density of flints recovered, on the surface, was indicative mostly of later activity from the middle to the end of the second millenium BC’. Personally, from these carefully chosen words and the fact that the whole of the Stonehenge landscape is soaked in the continuous activities of man from at least 8500BC, the door is still open to a ‘screen’ of sorts being in place here, contemporary to the chalk plaques I am contemplating.

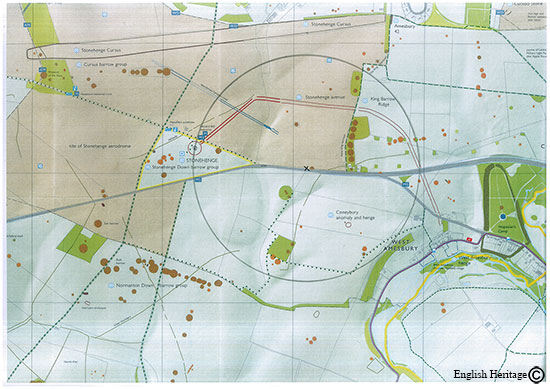

Recently, I discovered that the chalk plaque pit lies directly south of an original entrance to the Stonehenge Cursus, as I have previously written here, providing the ordnance survey coordinates. This coincidence inspired me to investigate more closely the location of the plaque pit, which sits in the overall Stonehenge landscape of its day. Attached below is an extract of the current English Heritage world heritage map of Stonehenge at a 1:10,000 scale, who obviously retain the copyright of the image.

The location of the plaque pit is marked with a small black cross centrally in the above image on the north carriageway of the A303. Another coincidence arises as follows:

- A radius taken from the plaque pit to the centre of Stonehenge also intersects the Avenue directly east of the plaque pit. I have drawn a circle on the above map to illustrate this.

Turning now to the image of the plaque, which I have inserted below the heading at the beginning of this post, I have highlighted in various colours the features that are represented:

- The Cursus is coloured green.

- The Avenue in red.

- The River Avon in blue.

- The wooden palisade to the left of the image in light brown.

- The four mesolithic pine posts (far left of the image) in the old visitor centre car park in brown.

- The location of the plaque pit is marked with a small black pencil cross, centrally on the plaque.

- I have also highlighted in brown an arrow type combination of incisions pointing south from the Cursus to the location of the Stonehenge monument site. This possibly indicates a movement in the focus of activity from the Cursus area to Stonehenge.

This possible ritual placing of the plaque at its location at commencement of work on the ditch and bank at Stonehenge may also be observed in traditions and myths surrounding foundation stones and cornerstones. The Roman god of bounds, Terminus, seems relevant here, bearing in mind the contents of the plaque pit which I described in an earlier posting. Beating the bounds is an ancient custom still observed in some English and Welsh parishes.

A ‘stone which supports the corners of the earth’?

“Where wast thou, when I laid the foundation of the earth?

Declare, since thou hast such knowledge!

Who fixed its dimensions, since thou knowest?

Or who stretched out the line upon it?

Upon what were its foundations fixed?

And who laid its corner-stone,

When the morning stars sang together,

And all the sons of God shouted for joy?

…Book of Job

The little-known wooden palisade to the west of Stonehenge (shown on the English Heritage map above) and east of the older Mesolithic area (marked as Mesolithic post holes on the map) creates a clearly defined separation of areas. At the time of the construction of the ditch and bank at the Stonehenge site it was 5500 years since the first pine post had been erected.

The above plaque is incised with a unique and complex array of markings that does not obviously fall completely within the style of British and Irish prehistoric rock art. As chalk is significantly easier to incise than rock, more complex imagery is capable of being portrayed, and these Neolithic pictograms surely deserve at least speculation over what may have been in the minds of the men and women who conceived and carved them 5000 years ago.

Probably the most famous example of Neolithic rock art is at Newgrange, which fit into 10 categories described here under art. The serpentiform, lozenge, chevron and parallel lines-type incisions are also displayed on the chalk plaque. The common circular and spiral type patterns of prehistoric rock art are not represented on the plaque. Ladders are portrayed on the plaque and feature too on the barmishaw and panorama stones on Rombalds Moor .

The tree of life on Rombalds Moor near Otley, West Yorkshire, appears welded into the landscape in the brooding images captured by Chris Collyer here and

History of Cartography here .