The Core Symbolism of Stonehenge

WRITTEN BY Austin Kinsley ON 06/06/19. The Core Symbolism of Stonehenge POSTED IN Stonehenge

Dr Terence Meaden Explains the Core Meaning of Stonehenge as Achieved by Shadow Casting of the Heel Stone upon the Altar Stone at Midsummer Sunrise

A guest post for Silent Earth prepared May 2019

In this blog the archaeological decoding of the fundamental symbolism of Stonehenge is explained.

The monument’s master plan was prepared by a Stonehenge architect about 2550 BCE, this being the reasonable date assignable to the raising of the biggest sarsen stones, which are in the middle of the monument. These biggest stones surround a central zone inside which the Altar Stone lies recumbent at the focus of the monument. The great sarsens of Stonehenge would have been set in place before the sarsen stones of the outer ring of lintelled sarsens.

FIRST, SUNRISE OBSERVATIONS MADE AT OTHER STONE CIRCLES

In a previous blog for Silent Earth here, the sophistication of the planning of Drombeg Stone Circle in County Cork was introduced and aspects of a new site survey discussed. Events at the spring and autumn quarter dates were considered in detail, together with crucially helpful photographic corroboration.

On the one hand there are the inbuilt positional features expected of an annual calendar that is based on eight repeatable dates that are always 45 or 46 days apart, starting with the winter solstice.

On the other hand, through recognition of the inherent dynamic and static symbolism at Drombeg, it provides spectacular drama of a much-loved mythical worldview which would have provided spiritual gratification to an expectant community as part of their religious philosophy and beliefs.

Moreover, the dynamic spectacles are still being witnessed by visitors today who arrive early enough in the morning to watch the relevant sunrises and events as they unfold. This happens in such a manner as to establish that the driving force behind the planning and construction at Drombeg was belief in a fertility religion.

The special enchantment of each occasion derives from watching the shadow motion produced by the light of the moving sun during the first minutes after sunrise. It results from the particular positioning of Drombeg’s perimeter stones that allow a series of shadows cast by pillar-like megaliths to fall upon either one or the other of two female-symbolic stones. One of these shadow-receptive stones is lozenge-shaped, the other is broad, flat topped and recumbent. The occasions are the eight festival dates known to us from Iron Age Celtic times. At Drombeg and other sites in Cork and Kerry recognition of these same dates is firmly proved for the Neolithic and Bronze Age, which were between 1000 to 3000 years earlier than the Iron Age.

The key is the hieros gamos, which is also known as the Sacred Marriage or the Marriage of the Gods. Similar effects apply to events staged at Stonehenge and at recumbent stone circles in Scotland and the particular multiple stone circles in Ireland that have an axial recumbent stone.

STONEHENGE: THE DRAMA OF THE UNION OF TWO CULT STONES AT MIDSUMMER SUNRISE

We now turn to the question of Stonehenge, which importantly also has a very well-known recumbent stone at its focus in the central area (Figure 1).

Figure 1 below: Crucial are the positions of the two most important stones at Stonehenge: the Altar Stone at the focus of the monument and the Heel Stone 80 metres distant in the direction of the midsummer sunrise.

On clear-sky mornings at Stonehenge in every midsummer week of the last 4500 years the sun shining on the externally located Heel Stone (Figure 2) has cast a shadow through the middle arch of the outer sarsen circle to reach the centre. The optimum situation occurs on the day of the summer solstice, although there is little difference for the sunrises from three days before and to three days after this date.

The master plan at Stonehenge turns on the importance of the positioning of two principal stones:

(1) The solitary megalith known as the Heel Stone which, when seen from the interior of Stonehenge, stands in the direction of the summer solstice sunrise north-east of the ditch-and-bank that encircles the monument (Figures 1 and 2). Its purpose is shadow casting with a symbolic intention.

Figure 2 below: The massive Heel Stone that casts a long shadow into Stonehenge at the summer solstice sunrise.

(2) At the focus point of Stonehenge is the Altar Stone. Its purpose is shadow receiving. It is located on the midsummer-sunrise axis, which itself bisects diametrically the interior of the circular monument (Figure 1, plan above). When freshly cleaned and wetted, this micaceous stone (Figure 3) sparkles in the light of the rising sun because of its myriads of tiny mica platelets.

The Altar Stone lies recumbent, horizontal, waiting for the male-symbolic shadow of the Heel Stone to arrive, which it does only in midsummer week. At no other time can the light of the rising sun penetrate to the centre of the monument.

Figure 3 below: Pressed into the ground by fallen sarsens is the stone that is at the focus of Stonehenge. Known as the Altar Stone, it is the primary Cult Stone.

The shadow has been witnessed from inside the middle of Stonehenge by Simon Banton (in 2013) and Terry Snailum (Meaden 2016: 162) among others. Terry Snailum wrote: “We saw that the tremendously long shadow cast by the Heel Stone and passing through the central trilithon … finished exactly upon the altar [next to] where we were sitting.” Simon Banton, viewing inside Stonehenge in midsummer week in 2013, reported: “I’ve observed the shadow penetrating the circle and I’ve calculated that it would reach the Altar Stone under perfect conditions.”

As David Field and six other colleagues well wrote (2015: 145), if sunrise observations from inside the monument were the intention then “the observation of solar events along the main axis could not have involved great numbers of people”.

Darvill and Wainwright (2009: 13) remark that so many perimeter and interior stones are set close to one another that when inside “they almost form a wall”. Indeed, only in midsummer week can the rising sun shine freely into the centre of the monument and arrive at the Altar Stone. Field et al. (2015: 145) add that the midsummer experience could only be appreciated by restricted numbers of people and “at Stonehenge just one or two may have witnessed the event”.

By contrast, if the greater idea was for an entire community of dozens or hundreds to appreciate and respect the occasion, then huge numbers of people standing near the Heel Stone outside the great circular ditch of Stonehenge could have witnessed the Heel Stone’s shadow entering the monument (Figures 1, 4, 5 and 6). Moreover, the small ring ditch (Figure 1, plan) centred by the Heel Stone would have kept the people getting too near the Heel Stone and its midsummer shadow, so as not to spoil the shadow-casting event for other devotees.

Figure 4 below: View from the interior of Stonehenge looking along the major axis as it would have been in midsummer week in Late Neolithic times. The sun was then rising to the left of the Heel Stone (cf. also the plan in Figure 1) whose shadow a few minutes later penetrated to the centre of the monument, as it still does at midsummer.

Figure 5 below: In midsummer week, the shadow of the Heel Stone is able to penetrate the monument soon after sunrise and reach the mica-bearing Altar Stone.

When watching from alongside the Heel Stone, I have viewed the shadow of the Heel Stone penetrating the circles of Stonehenge on several occasions at sunrise since June 1986. Also, in midsummer week 2016, Austin Kinsley and Pete Glastonbury filmed the long shadow cast by the Heel Stone entering the monument on its way to the cult Altar Stone.

What observers first see is the light of the rising sun shining past the Heel Stone (Figure 4). Four minutes later, on mornings when there is a clear-sky atmosphere, the strong shadow of the phallic Heel Stone is inside the monument (as in Figures 5 and 6). The photograph in Figure 5 was taken with the author seated and leaning back against the Heel Stone (but please note that this photograph results from a reconstruction when the documentary film for Channel 4 and Discovery Channel was being shot in 1998).

On the other hand, Figure 6 below is a true sunrise photograph from June 1989, but in which the shadow has been slightly darkened for purposes of clarity.

Figure 6 below: On this clear-sky morning in midsummer week June 1989, the writer saw the phallic shadow of the Heel Stone penetrating the female monument that is Stonehenge.

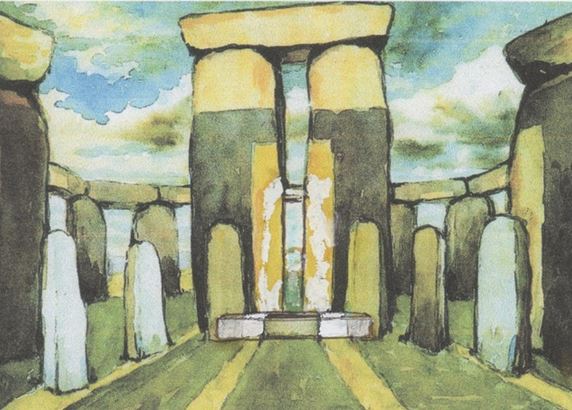

The shadow enters the medial arch of the outer sarsen ring and falls on the waiting micaceous Altar Stone. The interior is depicted in the painted reconstruction of Figure 7 to demonstrate these precious moments.

Figure 7 below: The Altar Stone was positioned to lie prone in the final phase of Stonehenge for nearly 1000 years from 2550 BCE. In midsummer week the shadow of the external Heel Stone reaches the Altar Stone soon after sunrise. (Commissioned oil painting by Maureen Oliver)

Unfortunately, occasions of a very clear atmosphere are uncommon. More often, the sun rises through haze and appears red and slightly dimmed. Nevertheless, it usually casts at least a faint shadow visible to the naked eye, although it can be difficult to photograph well. This is a primary point. Even a weak shadow can be seen by the human eye and this would have been good enough for apprehensive spectators of the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age who believed in the Mother Earth fertility religion of their epoch. After the shadow enters the monument, withdrawal occurs. Such is the nature of phallic detumescence. I have numerous Stonehenge photographs from 1986 onward that demonstrate this.

The ill-named Slaughter Stone that lies prone inside the external circular ditch has no relevance to the final-phase Stonehenge monument. There is good reason to suspect that this stone dates from an earlier period of use (pre-2550 BCE) in which it could have served a related purpose in the prehistoric drama (Meaden 2016: 181-182). Yet the stone was retained in a prone position out of respect for a former ancestral importance. It lies awkwardly in a trench cut for it that was not quite the right shape (Cleal et 1995: 285-287).

HOW THE ALTAR STONE LIES

It is important to know that the recumbent Altar Stone at the focus of the monument lies across the Stonehenge summer-solstice axis. Although it is precisely bisected by this axis, its own axial orientation is not perpendicular to the summer solstice axis. Instead, its angle of lie precisely matches the direction of the winter-solstice sunrise. This exactness suggests that the Altar Stone has not toppled haphazardly from some standing position but was deliberately laid flat at this location with the said orientation. Tim Daw and Simon Banton independently noticed this too. It further suggests — maybe via a kind of sympathetic spirituality — that there is another inbuilt pairing of stones in the monument that features and promotes the direction of the midwinter sunrise.

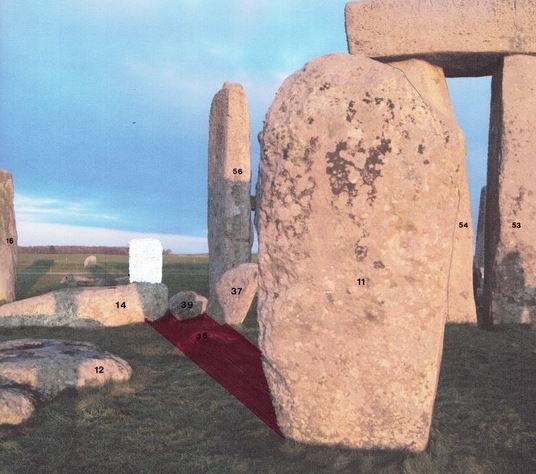

A study of a possible pair has been made in which the shadow-casting stone survives (Meaden 2016: 170-180). This is Stone 11 (see Figure 8).

Figure 8 below: At left, a view of the short phallic-like Stone 11 which now leans outwards.

Figure 9 below: These are Stones 10 and 11 of the outer sarsen ring.

At left is Stone 10, a normal standing sarsen of the outer circle, whereas Stone 11 is about half its height, half its width, half its thickness, and is round-topped.

ACTION AT THE WINTER SOLSTICE SUNRISE

In the outer sarsen ring is a puzzling stone, Stone 11, half the height, half the width and half the thickness of the others. It is round-topped and phallic shaped (Figures 8, 9 and 10). It stands half a metre out from the line of the otherwise perfectly circular lithic perimeter of the grand circle (Cleal et al.1995, see maps). This positional oddity, though minor, ensures that at sunrise on the winter solstice sunlight is able to fall upon this stone and throw a phallic shadow north-westwards.

The Welsh bluestone number 40 may be the stone that had been set up to receive the shadow at sunrise. Stone 40 is greatly damaged, but its base survives, located in its original setting (Figure 10). Furthermore, the self-orientation of this bluestone is anomalous in not being tangential to the circumference of the true circle of bluestones, but is, instead, angled in the direction of the summer solstice sunrise. This attribute is not fortuitous, seeing that it complements the behaviour of the orientation of the Altar Stone as a matter of mirrored juxtaposition.

Figure 10 above: This is a real photograph taken in December 2014 just after sunrise. The anomalous diminutive Stone 11 casts a shadow (enhanced by ink for purposes of clarity) at the winter solstice sunrise onto stones that are now fallen, damaged or removed. Introduced to the picture is a standing stone (shown white) to suggest the height of Welsh bluestone 40 at Position 40 if it was the original receptor stone and could be made to stand again where the sad broken stub of Stone 40 is now. The explanation could be that Stone 11 is a survivor, held in continuing respect, from an earlier epoch of the Stonehenge monument, and here being used or re-used in a helpful manner. Its position, awkwardly disturbing the perfection of the perimeter of the grand sarsen circle, shows that although the intention of the planners was to raise an outer ring of 30 sarsens, each with tenons and lintels, the monument was never finished. At most, 29 were raised, not 30, because old Stone 11 was in the way of any new lintelled stone.

As regards union by shadow at the midwinter solstice, this proposal between Stones 11 and 40 is explained in great detail in the downloadable paper: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/lithicstudies/article/view/1920

ACTION AT STONEHENGE AT THE WINTER SOLSTICE SUNSET

The point of sunset at the winter solstice is in opposition to that of midsummer sunrise as viewed past the Heel Stone when standing next to it. If the Altar Stone had lain flat in prehistory, then celebrants approaching Stonehenge from along the Stonehenge Avenue at the winter solstice sunset would have seen the sun setting within a narrow gap through the monument to the sunset horizon which is Normanton Down. If the Altar Stone had stood vertical, this view would have been blocked, so this further suggests that the Altar Stone did indeed lie flat.

THE HIEROS GAMOS

The hieros gamos is one of the highest levels of intellectual spirituality that has ever been recognized as part of ritual and worship in prehistoric times. The megalithic examples, identified at Stonehenge, Avebury and Drombeg for the Irish and British Neolithic Age, precede by up to two millennia the staged theatrical dramas of Sacred Marriage known for the era of the classical Greeks in south-eastern Europe and which were preceded in south-eastern Asia (as with the agricultural Sumerians known through cuneiform writings) much earlier than the Grecian literature. Among numerous scholars, Kramer (1969: 49) has examined the Sacred Marriage in ancient Sumer. His work should be consulted for its numerous references to places elsewhere.

CONCLUSIONS

What is certain about events at Stonehenge is that in midsummer week, centred on midsummer’s day, on clear-sky mornings, the shadow of the Heel Stone at sunrise enters the circular monument of Stonehenge and arrives at the recumbent Altar Stone. It has done so for 4500 years. I have witnessed it several times. Much care in the design plan and construction was necessary to ensure that this act of penetration would be watched as a moving spectacle. The choice and the exact positions of stones were important.

What does — and did — this signify?

A grand but simple and likely answer is that the design plan of Stonehenge developed from a community’s belief in hierogamy, when the Sky makes union with the Earth as part of a fertility religion. That is to say, the summer solstice is the portentous moment of the year for the occasion of the consummation of the classic Marriage of the Gods, uniting the Sky Father (in his epiphany of Sun God) with the Earth Mother. For this purpose the Heel Stone serves as the Sky God’s representative on earth. By linking features that symbolize the sexes, interpretation is viewed through the concept and desire for fertility, an understandable core feature of life for farming communities. The vision was heartening for the hard-working farmers who toiled the land and suffered the vicissitudes of changing fortune according to the times of arrival of seasonal and unseasonal weather.

Currently, the author is analyzing fieldwork data collected at over 40 Irish stone circles and ten Scottish recumbent stone circle sites. In a scientific research programme, the collection of factual data comes first, followed by a testable hypothesis and eventually theory as to the core meaning of, in this case, recumbent stone circles. Moreover, this research led to the rediscovery of what was a likely calendar used by the Neolithic and Bronze Age communities. This was unexpected. It is a day-by-day, whole-year calendar. Earlier studies of some 80 Wessex long barrows for an Oxford University MSc thesis have supported such a calendar too.

Francis Crick observed that “ … a theory will always command more attention if it is supported by unexpected evidence, particularly evidence of a different kind.” 1988, A Personal View of Scientific Discovery.

Phillip Kitcher, philosopher, 1983 said, “Good theories generate useful empirical predictions and give birth to new lines of inquiry often with an understanding of other phenomena which heretofore may have seemed unrelated”. This is one of several reasons why so many more stone circles are being studied. Predictions about alignments and stone positions are being readily made, and then tested and proved.

Karl Popper recognized this too: “ The more tests which can be made of the theory, the greater its empirical content.” 1959, The Logic of Scientific Discovery. 112, 267.

FINALE

Referring to the latest volume about Drombeg, Avebury and Stonehenge, the late Prof. Geoffrey Wainwright wrote to the author in September 2016: “I have read the volume with great pleasure. I found it a very stimulating book full of good ideas which made me think more deeply about the reasons which lie behind the planning of these monuments about which you write so eloquently. I hope that the book does well. It deserves to do so.”

Two peer-reviewed papers on this subject have been published, as well (Meaden 2017a, 2017b). Additional information about beliefs of the prehistoric peoples is available on my five Facebook timelines, together with the volume that treats the story of the universe, life, and prehistory and history of humankind, namely A New Bible in Three Testaments (New Generation Publishing, 2018).

References

Field, D., Anderson-Whymark, H., et. al. (2015). Analytical surveys of Stonehenge and its environs, 2009-2013: Part 2—the stones. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. Vol. 81, 125-148.

Kramer, S. N. (1969). The Sacred Marriage: Aspects of Faith, Myth and Ritual in Ancient Sumer. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University.

Meaden, G. T. (2016). Stonehenge, Avebury and Drombeg Stone Circles Deciphered for Their Core Symbolism. Saarbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Meaden, G.T. (2017a). Drombeg Stone Circle, Ireland: Design plan analyzed with respect to sunrises and lithic shadow-casting for the eight traditional agricultural festival dates and further validated by photography. Journal of Lithic Studies, Edinburgh University. Vol. 4, no 4, 5-37.

Meaden, G.T. (2017b). Stonehenge and Avebury: Megalithic shadow casting at the solstices at sunrise. Journal of Lithic Studies, University of Edinburgh. Vol. 4: no.4, 38-66.

Meaden, G.T. (2018). A New Bible in Three Testaments. London: New Generation Publishing. Amazon: £18.95 hardback; £13.95 soft-cover; £4.99 Ki