Iron Age Chalk Carving Maiden Castle Dorset

WRITTEN BY Austin Kinsley ON 06/12/17. Iron Age Chalk Carving Maiden Castle Dorset POSTED IN Dorset Neolithic Rock Art Stonehenge Incised Chalk Plaques

In February 1971, a young lad of fourteen years of age by the name of Timothy Roberts of Bristol was on a family visit to Maiden castle in Dorset. During the course of walking along the second (middle) bank on the southern side of the hillfort, he noticed the above carved chalk object protruding from the makeup of the bank, with its outer face towards the crest of the bank and ‘opposite the point where the ramparts curve inwards in conformity with the original defences of the eastern knoll’.

In an article on this chalk carving by Mr RAH Farrar, published in the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society Proceedings for 1974, Volume 96, published in 1975, Mr Farrar writes in respect of the date attributed to the object, ‘It may therefore be supposed to have been deposited either during or after the third phase of construction to which this bank belonged, in the remodelling of the defences ascribed to the mid second century BC’. He adds later in the article, ‘It is not always easy to assign a period to an object of this nature found out of secure context.’

Mr Farrar describes the carved chalk as:

- Eleven by nine centimetres.

- Naturally weathered smooth before use since the surface remains uneven.

- Incised to a varying depth of between one and two millimetres.

- V-sectioned cuts, although one side of the incision may be nearly vertical.

- Between four to five centimetres thick.

- The edges, mostly rough but probably the result of natural cleavage of the rock, show no signs of deliberate trimming, although the roughest edge might indicate deliberate fracture from a larger block.

- The reverse, however, bears irregular, channelled scorings over most of its rough but fairly flat face, much of them incised in much the same manner as in the obverse design, but some of them only lightly scratched. A short single groove of this kind also exists on the under edge.

The spiral form is portrayed in British and Irish prehistoric ‘art’ from the Neolithic onward, and also formed an early decorative motive in Celtic Christian art, for example, in the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Kells of the 8th and 9th centuries A.D., respectively. In Celtic Art in Pagan and Christian Times, published in 1904, John Romilly Allen writes, ‘Judging by the best evidence afforded by the dated specimens, the best kind of spiral ornament seems to have disappeared entirely from Celtic Christian art after the first quarter of the tenth century’.

In the central southern England region broadly known as Wessex, the discovery of any form of prehistoric ‘artwork’ across the Neolithic, Bronze Age or Iron Age, on stone, metal, chalk or other media, is particularly rare. What examples are there of how the artistic urge to ‘draw’ was expressed in this region in prehistoric times? A number of those examples that exist are outlined below:

On 1 November 1845, in the ‘immediate neighbourhood’ of Badbury Rings hillfort in Dorset, John Austen of Ensbury ‘accidentally ascertained that Badbury barrow’ was being levelled and recorded what he observed, which is summarised here at The Northern Antiquarian. The exact location of the barrow cannot be identified with certainty, but is said to be one of a small group in the parish of Shapwick. Mr Austen recorded his observations during the destruction of the barrow, along with Henry Durden of Blandford Forum, a well known antiquary. Mr Durden discovered a block of sandstone on which were carved images of axe heads and daggers. The stone is in the British Museum and a photograph of it is here. Andrew J Lawson, on page 253 of Chalkland writes of this dagger carving ‘Having been buried within the mound for more than three and a half millennia, the carvings on this boulder remain clear and provide support for the dagger interpretation of the Stonehenge carving’.

Below is a photograph, kindly provided by Neil Wiseman, of an axe and dagger carving on the NW interior face of stone 53 at Stonehenge, discovered in 1953 by Professor Richard Atkinson. The more recent graffiti at the top of the photograph is confirmed by Simon Banton as ‘IOH : LVD : DEFERRE’ and Neil Wiseman adds ‘John Louis Deferrere may have been a visitor to Amesbury from Paris in 1755. Whoever it was, was right-handed, knew Latin abbreviations, and had the patience of a saint, that carving would have taken quite a while to do!’

In the English Heritage research report series no.32-2012 laser scan, the report concluded that ‘The only convincing carvings on Stonehenge are of axe-heads and daggers. In total 115 possible or certain axe head carvings and three dagger carvings have been identified.’ These dagger carvings are generally accepted as attributable to the Bronze Age.

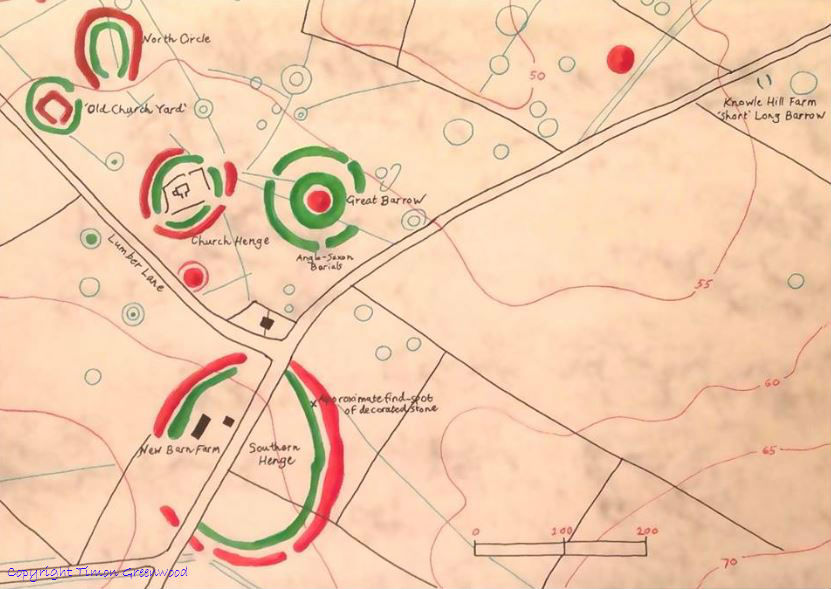

Approximately 47 years ago, two large stones were ploughed out of the southern henge at Knowlton in Dorset and it has been suggested that the stones came from the bank of the southeastern section of the henge. One of the stones had ‘artwork’ on it. An article on the subject can be found here. Recently, Mr Tony Hack was kindly given permission to photograph the stone by Dr Martin Green, which is gratefully reproduced below. A possible Neolithic dating has been suggested for this carving in ‘Past’, the newsletter of the Prehistoric Society here.

Below: The lesser known southern henge at Knowlton in Dorset is largely ploughed out. Timon Greenwood has kindly provided this illustration highlighting the location of the discovery of the decorated stone on the bank in the south eastern section.

Below: Church Henge Knowlton Dorset.

An incised stone bearing similarities to the above stone was discovered in Winterborne Came barrow in Dorset in the mid 19th century and an illustration of it from 1867 is included in this article at The Northern Antiquarian.

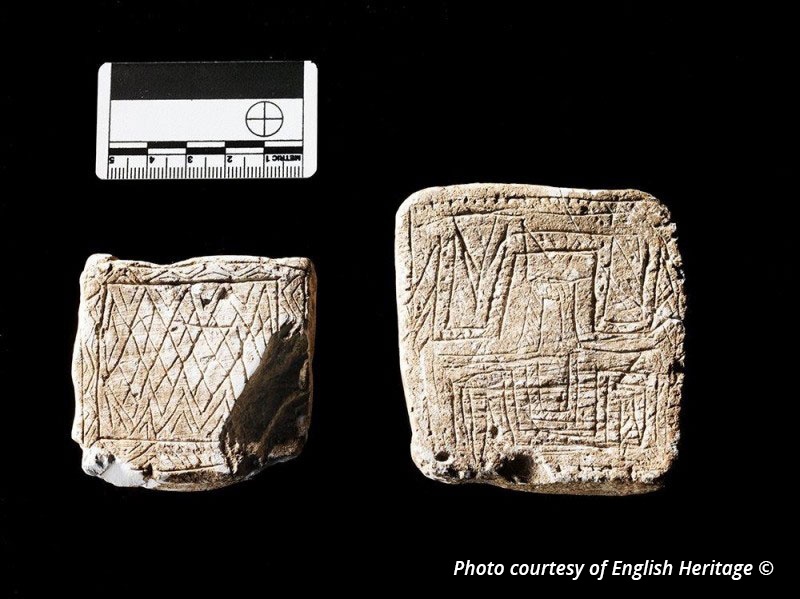

The ‘Stonehenge’ chalk plaques in the photograph below were discovered between King Barrow Wood and Stonehenge Bottom in the late 1960s by Major HM and Mrs. F De M Vatcher. They were found during the widening and lowering of the A303 road near Stonehenge in the chalk of the verge on the north side of the carriageway, 211 yards west of the wood. The plaques were found near the base of the pit at a depth of a little under two feet from the surface. The upper part of the ditch filling was empty of finds and compacted, consisting of red-brown soil and fine chalk nodules. An antler pick sat on top of the lower layer near a small scapula, thought to be that of a sheep. Sherds of grooved ware and various animal bones were found throughout the lower layer. A number of small grooved chalk lumps were also found. It was concluded that the upper layer of the pit was filled soon after the placing of the goods in the lower layer, as the sides were not weathered. At the time of discovery broad comparisons were made to Iberian clay and schist plaques, although no similarity of design or purpose were identified. Holes were bored in the corners of many of the Iberian examples, which is not evidenced here. The chalk plaques are dated by English Heritage at between 2900 BC and 2580 BC, placing them firmly in the Neolithic.

In her opus Windmill Hill and Avebury Excavations by Alexander Keiller 1925-1939, Isobel Smith writes:

‘The soft chalk, easily carved or marked by flint tools, afforded an opportunity for the expression of artistic impulses and symbolism otherwise scarcely represented in the surviving remains of Neolithic cultures in southern England. The forms recognised comprise ‘cups’ with large or small hollows; blocks and smaller pieces with hour glass perforations; balls; representations of the human figure and the male generative organ; incised pieces; ‘scrapers’; and a number of unclassifiable objects, mainly fragmentary, that have been artificially shaped or smoothed. It is doubtful whether any of these were designed to serve utilitarian purposes’.

Below is a photograph kindly provided by Pete Glastonbury of one of the chalk objects discovered by Alexander Keiller during his excavations on Windmill Hill near Avebury in Wiltshire and in the archive at the Alexander Keiller Museum at Avebury. This item is described by Isobel Smith as ‘Chalk amulet with incised designs and incomplete perforation’. Windmill Hill is an example of a Neolithic Causewayed enclosure which English Heritage indicate was built around 3675BC and the site remained in use until around 2500BC. This chalk carving may therefore be contemporary with a date range 3675-2500BC.

Below is a chalk object found by Pete Glastonbury on Windmill hill near Avebury in Wiltshire, exhibiting certain similarities to the amulet above.

On Fyfield Down, east of Avebury in Wiltshire, recumbent among a natural drift of sarsen stones, is a cup-marked sarsen stone apparently first recorded by the archaeologist AD Lacaille in 1962. An article on this particularly rare example of a cup-marked stone in southern Britain can be found here at The Northern Antiquarian. Pete Glastonbury has kindly provided a photograph below of the stone.

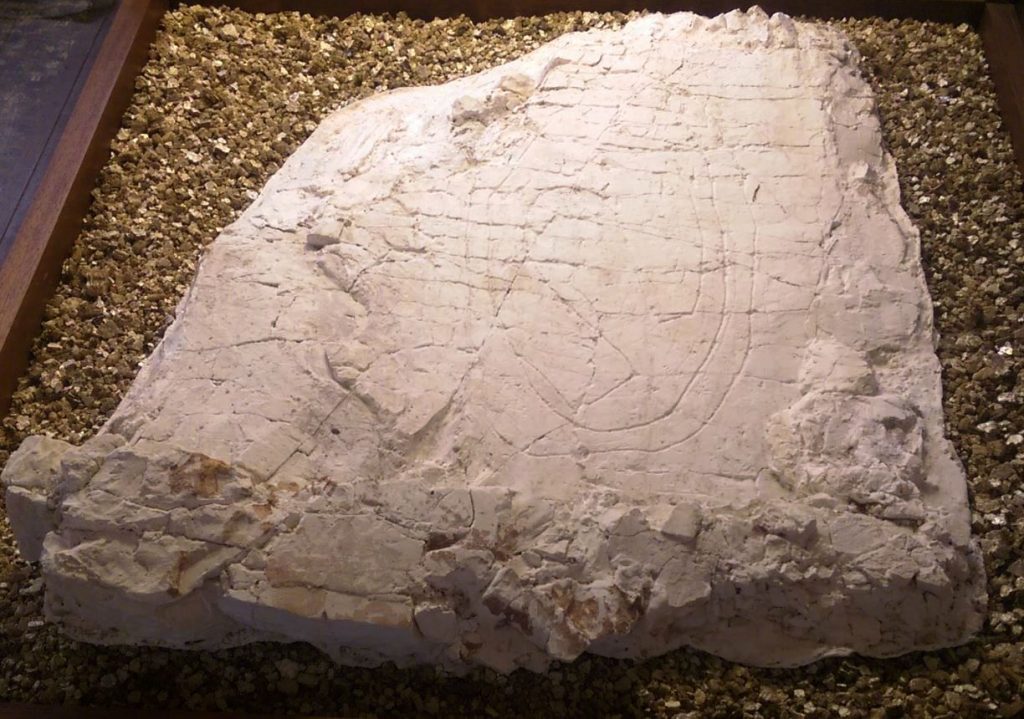

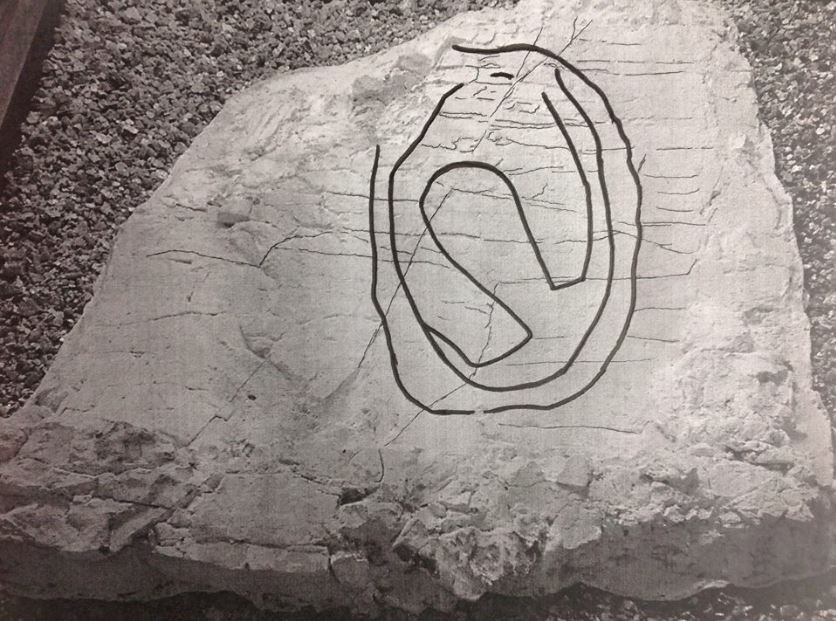

Displayed in Dorset County Museum is the large slab of chalk photographed below, which once formed part of a vertical wall in a ditch segment of Flagstones Henge, which stood underneath what was later to become the house of the famous Wessex author Thomas Hardy at Max Gate in Dorchester. In his book Stonehenge, Professor Mike Parker Pearson writes on page 318 that ‘the little known Flagstones lies at the heart of a Neolithic ritual landscape, surrounded by the remains of burial mounds and three large monuments’. He also states, ‘Flagstones has one thing that Stonehenge does not: using flint flakes, someone in the Neolithic carved pictures into the vertical chalk sides of its ditch segments in four separate places. This art was very basic: concentric circles, a meander motif, criss-cross lines and parallel lines’.

Professor Mike Parker Pearson indicates further on page 318 of his above book that ‘Flagstones henge ditch was dug in the period 3300-3000BC’. It is not unreasonable to assume therefore that this carving on the vertical chalk sides of the ditch was carried out too at approximately that time.

And from above:

Below: I am currently studying the Flagstones incisions in greater detail along with Timon Greenwood who has kindly provided the image below, adding: ‘I have only drawn over the deepened incisions, not the quick, sketched ones so far. It is really interesting to me that someone appears to have rapidly scratched out the more circular designs and then gone in hard to do the framed horseshoe shape.’

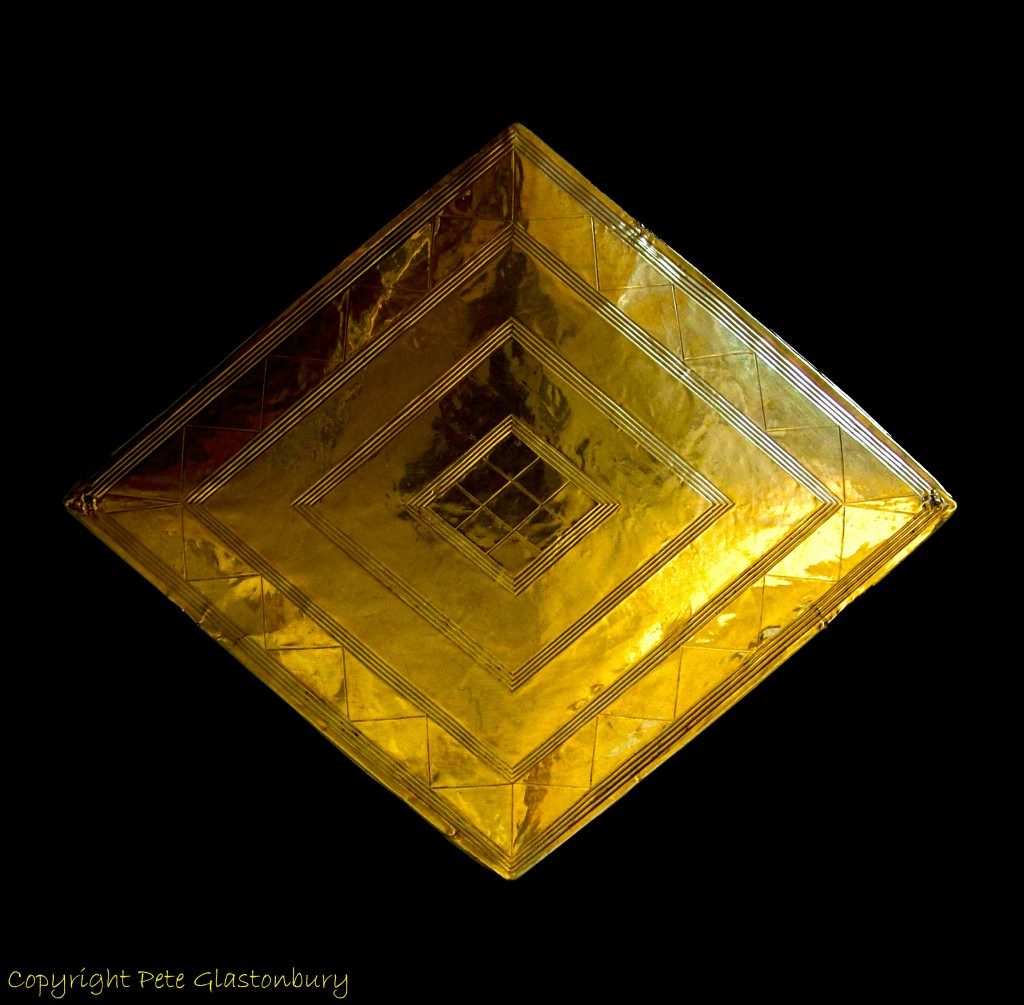

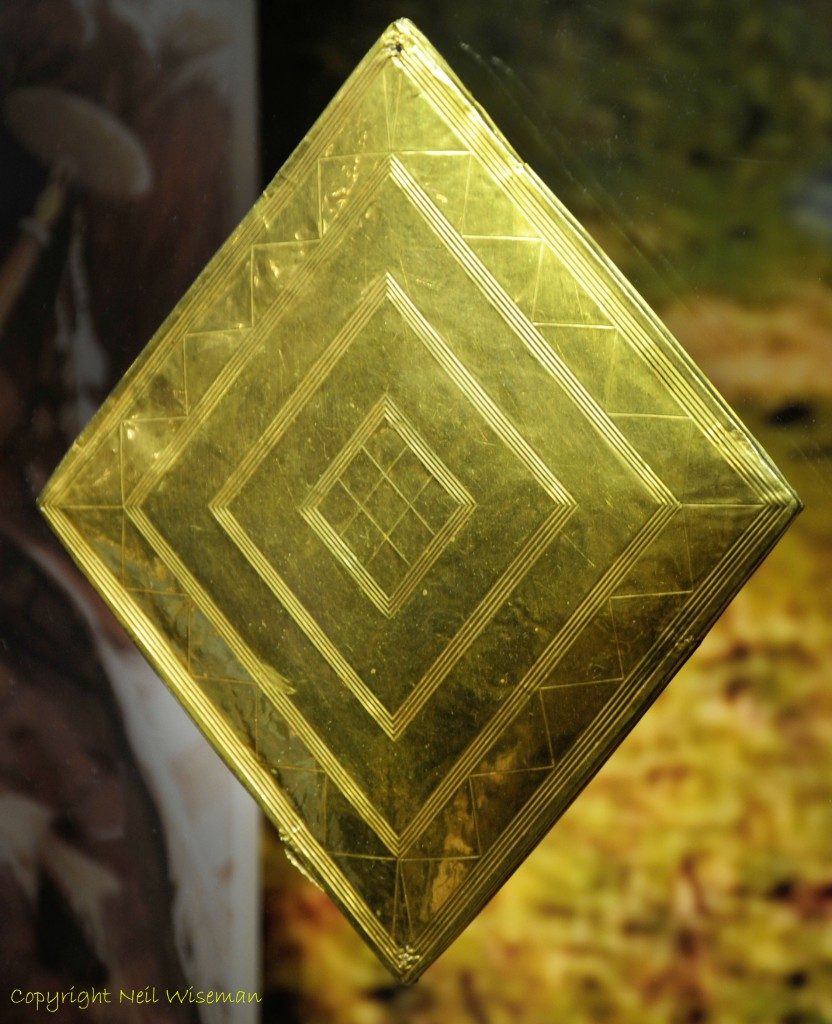

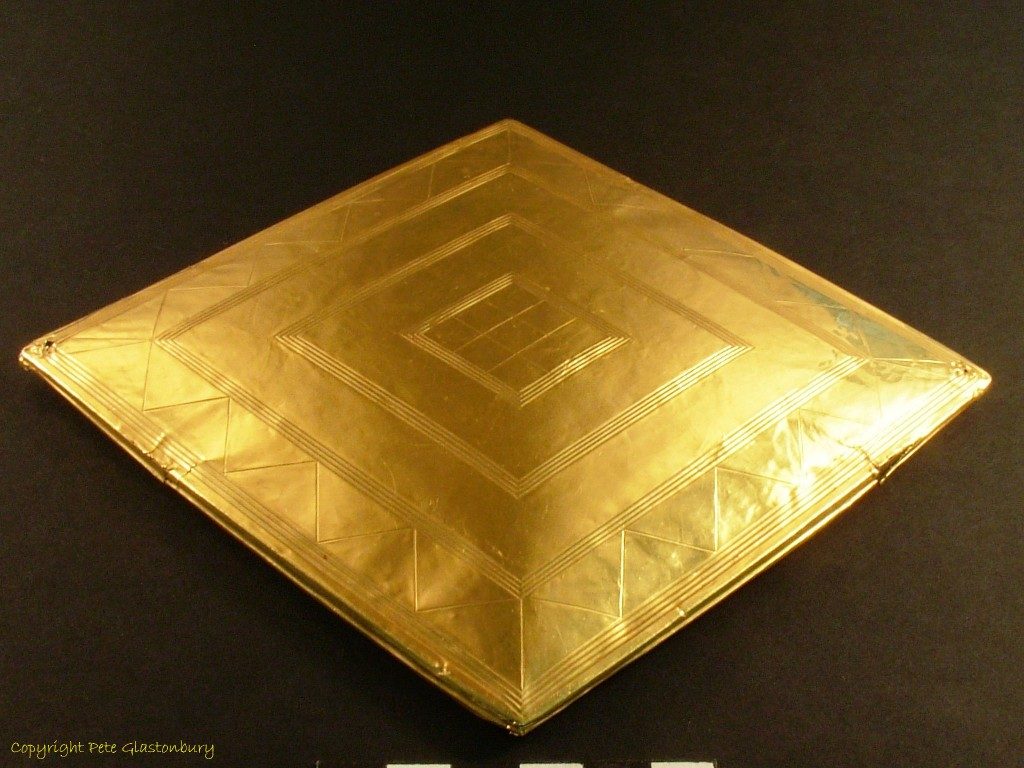

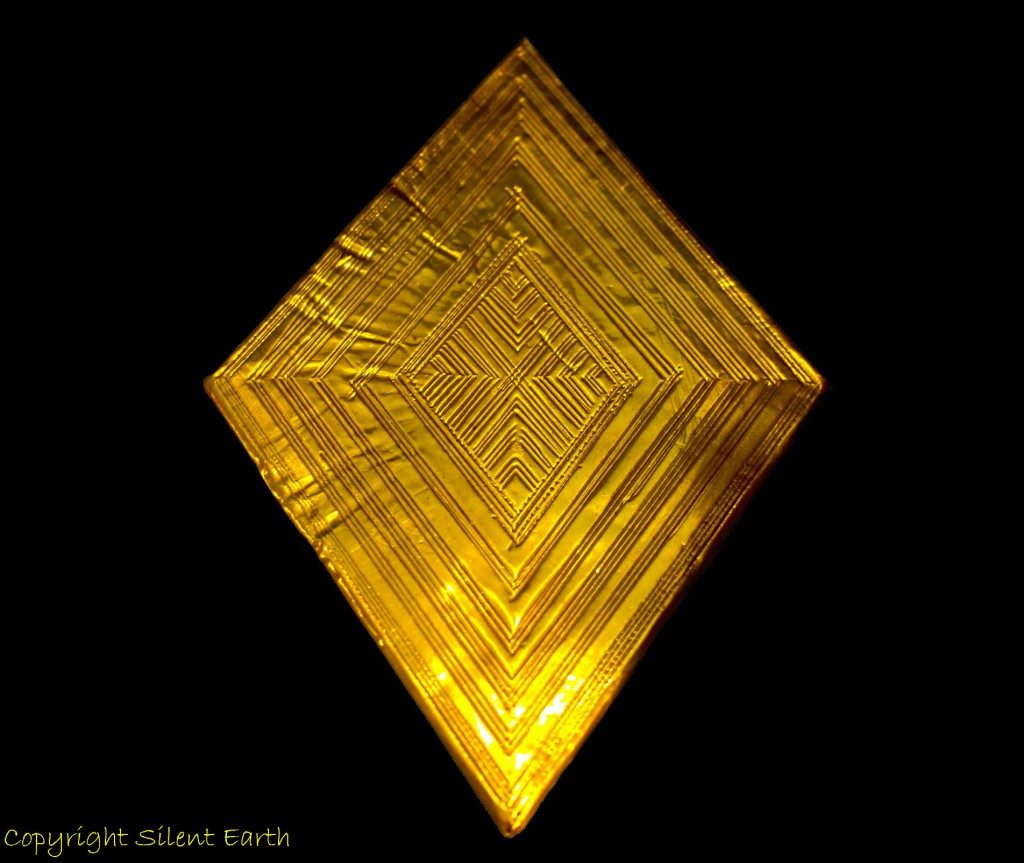

In 1808, under the patronage of Sir Richard Colt Hoare, a Bronze Age barrow was excavated in the Stonehenge landscape on Normanton Down, resulting in the discovery of the now-famous ‘Bush Barrow Lozenge’ and described in Sir Richard Colt Hoare’s published words as: ‘Immediately over the breast of the skeleton was a large plate of gold, in the form of a lozenge, and measuring 7 inches by 6. It was fixed to a thin piece of wood, over the edges of which the gold was lapped: it is perforated at top and bottom, for the purpose, probably, of fastening it to the dress as a breast-plate. The even surface of this noble ornament is relieved by indented lines, checkers, and zigzags, following the shape of the outline, and forming lozenge within lozenge, diminishing gradually towards the centre’. Thank you Pete Glastonbury for the photograph below of the lozenge, on display at Wiltshire (formerly Devizes) Museum.

Below: Bush barrow lozenge courtesy Neil Wiseman

In a letter to his patron, Sir Richard Colt Hoare, William Cunnington who excavated Bush barrow, wrote: ‘We found the skeleton of a stout and tall man. On approaching the breast of the skeleton we found immediately on the breast bone a fine plate of gold. This article in the form of a lozenge was fixed to a thin piece of wood, over the edges of which the gold was wrapped.” There was a large golden belt-hook lying by his waist, which was decorated with delicate impressed linear lines, as well as another smaller diamond shaped lozenge’. The barrow cemetery on Normanton Down has been dated to the early Bronze Age.

Below is the lesser known sibling of the above Stonehenge Bush barrow lozenge, the Bronze Age Clandon Barrow lozenge. It was discovered on a hill above Martinstown, a village close to Dorchester in Dorset, in 1882 by Edward Cunnington while he was excavating a Bronze Age barrow, and is now on display along with a replica in Dorset County Museum. Of this gold lozenge-shaped plate, the museum writes ‘The precision and accuracy if its decoration suggests sophisticated tools and knowledge of geometry. The gold probably originated in Ireland’.

These gold lozenges are endlessly fascinating and I will return to this subject along with the other gold objects discovered in Bush barrow an upcoming blog post.

Returning to the initial subject of this article — the Iron Age chalk carving found at Maiden castle in Dorset in 1971 by Timothy Roberts, on display at Dorset county museum — the museum states, ‘Found in the south ramparts of Maiden Castle, the spiral – a common decoration in prehistoric art – suggests a human face’. Looking at the double spiral incised on this object perhaps suggestive of human eyes, there is a broad similarity to the double spiral recorded in detailed sketches in a 1957 article by Forde-Johnson, (mentioned here by The Northern Antiquarian) on stone e of the Calderstones. Timon Greenwood has kindly reproduced the original sketch below, as I have unfortunately not been able to locate a photograph of this elusive Megalithic artwork on stone e of the Calderstones.

During 2017, excavations by Dr Jim Leary and the University of Reading at Cat’s Brain Neolithic long barrow in Wiltshire, two decorated chalk blocks that had been deposited into a posthole during the construction of the timber hall were discovered and described by Dr Leary in this recent article. Dr Leary writes: ‘The decoration on these blocks comprises deliberately created depressions and incised lines, which have wider parallels at other early Neolithic sites, such as the flint mines of Sussex. Controversy often surrounds decorated chalk pieces; chalk is soft and easily marked and some people suggest that they are “decorated” with nothing more than the scratchings of badgers. But there is no doubt that the Cat’s Brain marks are human workmanship and the discovery should spark a fresh investigation into decorated chalk plaques more widely. For the moment, the original purpose of the carvings remains obscure, but clearly they were of significance. They will have had meaning and potency to the people that created them, and by depositing them in a posthole the building itself may have been imbued with that power, as well as marking it with individual or community identity’.

In a brief summary, how do the above disparate examples “art” incised on various media dated from the earlier Neolithic to the Iron Age from the region of southern England broadly known as ‘Wessex’ inform us:

- Incising and carving on chalk is demonstrated from the early Neolithic and a higher number of dateable examples of incisions on this media appear to exist in the Neolithic rather than the later Bronze and Iron ages.

- Badbury barrow in Dorset is the only site other than Stonehenge that exhibits BOTH axe head AND dagger carvings indicating perhaps a close tie between the Bronze Age peoples of these regions within the Wessex environs seperated by 34 miles on modern day roads.

- The decorated Knowlton stone exhibits similarities to Neolithic megalithic art found in the classic areas of Ireland and other parts of Britain and is a particularly rare example in Wessex.

- The exquisite gold work of the Bronze Age lozenges illustrate a knowledge of geometry and, if the gold of the Clandon Barrow lozenge originated from Ireland, possible commercial links between Wessex and Ireland had been established by that time. These iconic objects are without parallel and demonstrate the pinnacle of Bronze Age incision work on the most highly prized and highest status media — gold.

- The Iron Age chalk carving discovered by Timothy Roberts at Maiden Castle in Dorset, although tentatively dated to the Iron Age, does not neatly fall into any ready category, making it perhaps all the more interesting. The closest geographical similarity in spiral form is the elusive Calderstones double spiral on a stone which once formed part of a burial chamber covered by a large earthen mound set up in the late Neolithic period, with the site being reused in the Bronze Age.

Thank you to those who have contributed photographs’ illustrations and editing for this article: Tony Hack, Timon Greenwood, Pete Glastonbury Neil Wiseman and Aynslie Hanna.