As a child, I enjoyed many family summer holidays in the West Country, particularly in the area around St Merryn, Trevone Bay, Constantine Bay and Harlyn in Cornwall. Living on the south coast of England in Bournemouth, Dorset, the drive across the ‘green and pleasant land’ of Dorset, Devon, and Cornwall was unfailingly an inspiration. In recent years, I generally visit Glastonbury in Somerset three or four times a year, and to this day, driving west from Bournemouth somehow naturally lifts my spirits, perhaps in echo of those halcyon days of sunshine, seaside, innocence and childhood.

My first drive to Glastonbury in 2016 was on Sunday 13 March, accompanied initially by a perfect early spring blue sky. By mid-afternoon, as I walked from the town to Glastonbury Tor, a light mist was rolling in and rising across the Somerset Levels.

Above: Walking east along Dod Lane and commencing the ascent of Chalice Hill beyond, this is the view looking west across Glastonbury town. The skyline is dominated by the Church of St. John the Baptist.

Above: A final rise in Chalice Hill looking here to the southeast before the summit and first sight of Tor Hill and St. Michael’s Tower.

Above: A first glimpse of Tor Hill and St. Michael’s Tower to the southeast, shrouded in a light afternoon mist. Before modern drainage, Glastonbury Tor in winter would have towered as an island above the flooded Somerset Levels.

‘Of all the trees that grow so fair, old England to adorn, greater are none beneath the sun, than oak and ash and thorn.’ – Rudyard Kipling.

St. Michael’s Tower on the summit was part of a 14th century church. It was built to replace a previous church which had been destroyed by an earthquake in 1275. The second church lasted until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539. Richard Whiting, the last Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, was hung, drawn and quartered at the tower along with two of his monks, John Thorne and Roger James; more here and here.

In 1786, Sir Richard Colt Hoare of Stourhead bought the Tor and funded repair of the tower in 1804, including the rebuilding of the northeast corner. It was passed down through several generations to the Reverend George Neville and included in the Butleigh Manor until the 20th century. In was then bought as a memorial to a former Dean of Wells, Thomas Jex-Blake, who died in 1915.

The National Trust took control of the Tor in 1933, but repairs were delayed until after World War II. During the 1960s, excavations identified cracks in the rock, suggesting the ground had moved in the past. This, combined with wind erosion, started to expose the footings of the tower, which were repaired with concrete. Erosion caused by the feet of the increasing number of visitors was also a problem and paths were laid to enable them to reach the summit without damaging the terraces. After 2000, enhancements to the access and repairs to the tower, including rebuilding of the parapet, were carried out. These included the replacement of some of the masonry damaged by earlier repairs with new stone from the Hadspen Quarry.

St. Michael’s Church survived until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539 when, except for the three storey tower, it was demolished. The surviving tower has corner buttresses and perpendicular bell openings. There is a sculptured tablet with an image of an eagle below the parapet.

Above: The path less travelled, running east of the southern end of Bulwarks Lane and the northerly tip of Lypyatt Lane. From the summit of Glastonbury Tor at 520 feet, three counties, Somerset, Dorset and Wiltshire, can be viewed.

Above: Approaching Tor Hill and St. Michael’s Tower from the northwest. ‘Tor’ is a West Country word of pre-Roman origin. The conical shape of the Tor is natural, due to its rocks. It is made up of horizontal bands of clay and limestone with a cap of hard sandstone. The sandstone resists erosion, but the clays and limestone have worn away, resulting in the steep slopes.

Above: This Millennium standing stone is located at the beginning of the northeastern pathway to Glastonbury Tor in Moneybox Field. The stone is 6ft high and tells us that Wells is 8 miles away. It is said the Tor and the red and white springs at its base have been a place of pilgrimage for over 10,000 years.

Above: The entrance to a lesser known and enchanting apple orchard named ‘Avalon Orchard’ on the eastern terraces of Glastonbury Tor and, if I may dare to dream for a moment, perhaps where can be found from time to time the sacred apple tree of the Isle of Apples guarded by its dragon. Four orchards on the lower slopes have been re-planted with cider apples, growing the traditional Somerset varieties of Kingston Black and Yarlington Mill.

Above: A cloutie tree on a southern terrace of the Tor and in the foreground, the ‘Egg Stone, or Tor Burr, which seems to be a natural outcropping and it has been suggested that it is the termination point of the so called labyrinth’ (quote courtesy of Paul ‘Beastie’ Baker).

Above: The cloutie tree looking southeast.

Historic England on Pastscape here, on the subject of earthworks, states: ‘Glastonbury Tor has been interpreted in at least three ways. Originally these were thought to be Medieval strip lynchets, however it has been noted that the top of the Tor is too steep for effective cultivation with or without animals. It suggests if these were lynchets it was during a time of extreme land-hunger that forced people to marginal land. It is known that the lower terraces at least were cultivated, as seen in a drawing of 1670 which has sharp contrast to the wilder terraces above. This cultivation remained until at least the 19th century.

Another theory was that of a spiral maze, in a similar if very elongated pattern to those found elsewhere dating to the Iron Age. This is a strong idea in popular culture but ultimately unlikely to be the explanation as it is rather too subjective and it would be unusually placed.

It is possible that the terraces are Neolithic modifications of the natural Tor. The Tor is visible from around the landscape and would have been an important landmark so it is not unlikely it would have been modified by the people living in the surrounding area. Later on the lower terraces were cultivated and the upper ones left due to their unsuitability. It is also likely that they have seen other uses throughout their history although there is no evidence for this.’

A more detailed archaeological assessment by Somerset County Council is here.

Above: On Sunday 13 March 2016 as the sun began to sink low in the western sky, people began to gather on the summit of the Tor to observe the sunset, as has probably been the case since time immemorial.

Above the Western side of St. Michael’s Tower.

Above: The view from inside St. Michael’s Tower looking west just before sunset Sunday 13 March 2016.

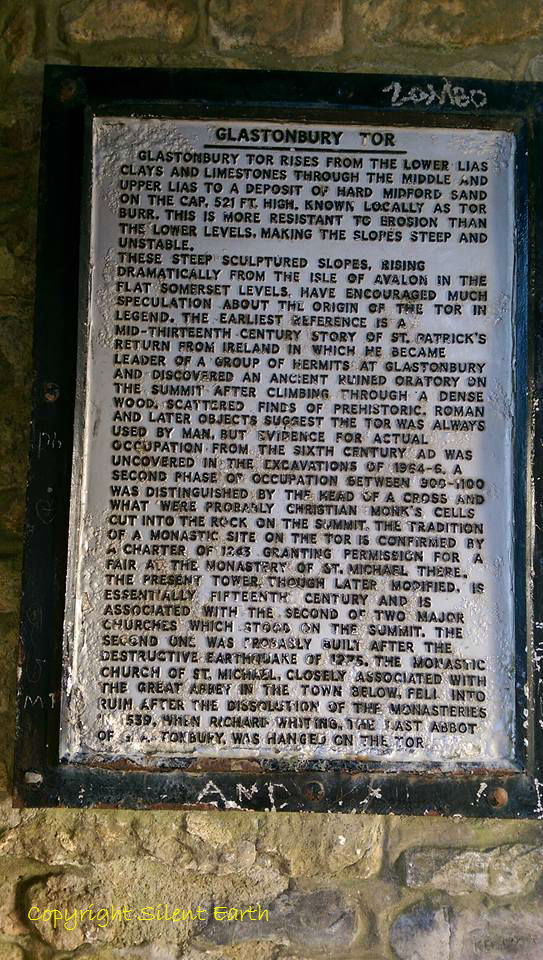

Above: An historical plaque inside St. Michael’s Tower.

Above: The approach of sunset, somehow naturally a time for silence and reflection.

Time to descend the Tor, return to Glastonbury town and a car journey east, to Bournemouth and home.