Professor Alasdair Whittle concludes the forward of the English Heritage seminal 2013 publication Silbury Hill: The Largest Prehistoric Mound in Europe with the following observation: ‘Was this the willed vision or the planned creation of a particular group, a lineage say, or a dynasty, or a sect of charismatic sages, who mobilised and motivated the labour for this astonishing construction over a very small number of generations in the rapidly changing circumstances of their times?’

Silbury Hill near Avebury in Wiltshire was probably completed around 2400 BC and is situated at the source of the River Kennet, a major tributary of the River Thames. It is approximately 131 feet high and stands as a truncated cone close to the valley floor. It does not appear above the skyline of surrounding hills and although visually inconspicuous from a distance, its sheer bulk becomes apparent when approached.

Writing in the mid-17th century, John Aubrey recorded the local tradition that King Sil or Zel, was buried there on horseback and the mound was constructed over his grave and ‘raysed while a posset of milke was seething.’ Human bones, along with horse-riding equipment, were discovered on the summit around 1723. In 1743, William Stukeley, the antiquarian, recorded:

‘workmen dug up the body of the great king there buried in the centre, very little below the surface. The bones extremely rotten, so that they crumbled them in pieces with their fingers … Some weeks after, I came luckily to rescue a great curiosity, which they took up there; an iron chain, as they called it, which I bought of John Fowler, one of the workmen; it was the bridle buried along with this monarch, being only a solid body of rust. I immerg’d it in limners drying oil, and dry’d it out carefully, keeping it ever since very dry.It is now as fair and entire as when the workmen took it up … There were deer horns, an iron knife with a bone handle too, all excessively rotten, taken up along with it … Our bridle belonged to the harness of a British chariot…’

The bridle has subsequently been dated to the 11th century and the burial (if associated) is assumed by English Heritage to be of similar date.

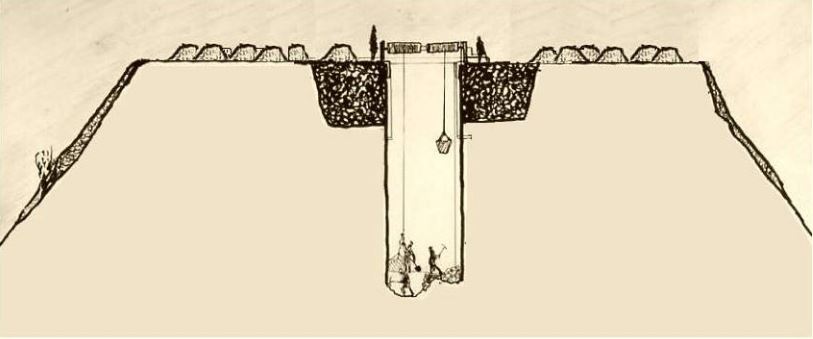

In 1776 Colonel Edward Drax used a team of miners from the Mendip hills in Somerset to excavate a vertical shaft from the top of the mound, but no clear records of this excavation exist. (Brian Edwards 2010 article published in Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine ‘Silbury Hill Edward Drax and the 1776 excavations’ is here.) There is, however, a reference in 1793 by Revd. James Douglas in Nenia Brittannica stating ‘The only relic found at the bottom, and which Colonel Drax showed me, was a thin slip of Oakwood’. Drax wrote in letters in 1776 discovered by Brian Edwards in the British Library: ‘Still as we go down we continue finding pieces of deer horns of a very large size in all appearance either of large stags or else the moose deer.’ He wrote that these horns were found at 23, 28 and 30 feet from the summit. He also recounted in a second letter in 1776 (again discovered by Brian Edwards) his observations of an incident as the tunnel reached 95 feet from the summit, (approximately within 5 feet or so of the natural ground level): ‘We struck upon a thing which I am sanguine enough to hope will lead to a great discovery. It was a perpendicular cavity that as yet appears bottomless. It is just 6 inches over; we have followed it already about 20 feet; we can plumb it about eleven feet more but as a great deal of loose chalk has unfortunately fallen in, at that depth, is a stoppage but as at present a strong wind comes up the hole enough almost to blow out a candle, it must have some communication with the air or some great cavity somewhere. At first what the miners call a damp or foul air came out of it into the shaft so that they could hardly breathe nor would a candle burn, but that is over and now a strong wind comes up; as it is in the very centre of this great hill and goes perpendicular down, it is matter of astonishment. The country people when we were at work at the barrow said that on the hill opposite on the other side of the River Kennet, on a great Long Barrow (West Kennet Long Barrow) set round with stones, the people at work there to get the stone had discover’d a great hole which they always had an opinion had a communication under Silbury Hill’.

The Central Committee of the Archaeological Institute arranged for an investigation of the mound in 1849. A tunnel was dug from the south of the mound below the original land surface. The Very Revd. John Merewether, Dean of Hereford Cathedral, recorded that the tunnel broke through the original land surface at a distance of 33 yards from the tunnel entrance. Here the mound was composed of ‘brownish aerh chalky rubble’ and this level was subsequently followed to the centre of the mound where ‘sods of turf and moss in layers appeared to be of the greatest thickness … curving layers of turf lying one over the other’ were found. ‘The turf was quite black, as was also the undecayed moss and grass which formed the surface of each layer, and amongst it were the dead shells etc’. The Reverend also recorded ‘many sarsen stones were discovered’ and suggested that they provided a kind of peristalith ( a ring of upright stones around a mound or dolmen). The only finds were fragments of antler and a few animal bones from the body of the mound.

The mound was one of the first monuments in Britain to be protected under the Ancient Monuments Act 1882.

In 1997 Professor Alasdair Whittle refined the developmental sequence of the mound, initially formulated by Professor Richard Atkinson in 1968, into 11 distinct phases as follows:

- Central gravel mound

- Turf stack edged by stake holes and perhaps small sarsen stones

- Four alternating capping layers over the turf stack

- A dump of chalk and clay

- Chalk rubble dump

- Another chalk and clay dump

- Further chalk and rubble dumps

- Again chalk and clay dump

- Chalk rubble

- Infilling of buried ditch

- Outer chalk layers

The presence of sarsen within the mound is confirmed in recent work and was mentioned on three other occasions during excavations, by Merewether, Petrie and Atkinson. No sign of a sarsen peristalith is currently visible.

At various points around the slopes are traces of horizontal terraces, platforms or breaks of slope. The uppermost of these ledges, a maximum of 2.5m wide on the surface, lies 4 metres below the summit. A second ledge or terrace can be traced at approximately 10 metres below the summit and stretches of breaks of slope that might account for others lie at 15, 19 and 27 metres below the summit. If perambulated, the upper ledge finishes the circuit at a position below the starting point and implies a spiral arrangement. Terracing could have formed a spiral ascent of the hill. A spiral would initially allow easy access and material could be relatively easily carried or dragged up to the working level. As a finished monument, a spiral arrangement would have provided a perfect processional way. If it is a spiral, it is arranged clockwise ‘sunwise’ from the top downward, and one would ascend anticlockwise ‘widdershins’.

Other platform-like features are are situated around the mound, both on the slopes and close to the original ground level, which remain undated. In the west are two 2m wide sub-rectangular platforms that stretch for 12 metres which are of unknown purpose but could have held structures. The present pathway to the summit, eroded and hollowed in places, curves around the western slopes, starting opposite the southwestern causeway, and dates from at least 1663.

There is an external ditch in the south and east, the sides are steeply cut compared to the north, where the outer edge of the visible ditch is quite shallow, resulting in a broad flat bottom up to 43 metres across.

Below: A platform-like feature on the southwestern side of Silbury hill can be seen on the right-hand side, also referred to as a ‘spur’.

After a hole appeared in the summit of Silbury hill in 2000 and following subsequent collapse, excavations and repairs were carried out between May 2007 and May 2008, during which English Heritage refined the interpretation of the various phases of construction, which broadly summarise as follows:

- Phase 1 natural deposits underlying the old land surface

- Phase 2 old land surface

- Phase 3 gravel mound

- Phase 4 low organic mound and mini mounds

- Phase 5 pits

- Phase 6 upper organic mound

- Phase 7 bank and ditch

- Phase 8 bank 2

- Phase 9 bank 3

- Phase 10 bank 4

- Phase 11 bank 5 and later organic layers

- Phase 12 the infilling and backfilling of ditch 1, and cutting of ditch 2

- Phase 13 the backfilling of ditch 2 and cutting of ditch 3

- Phase 14 the infilling of ditch 3, and cutting of ditch 4

- Phase 15 the backfilling of ditch 4

- Phase 16 final mound construction

Of the stone incorporated in the hill are four struck flakes of spotted dolerite (bluestone) recovered from the summit. All the fragments are from subsoil or topsoil, and a prehistoric origin for them has been suggested by English Heritage to ‘remain a possibility’. A piece of rhyolite was also recovered in the nineteenth century from a Roman well near the base of Silbury hill, which on analysis by Dr. Rob Ixer ‘is one that has not been recognised from either the extant orthostats or debitage from Stonehenge’. In respect of the four dolerite fragments from the summit, he concludes ‘Their petrography is the same as most of the Stonehenge orthostats and their size and shape are consistent with the smaller preselite debitage from Stonehenge’.

Forty-six sarsen stones weighing 779.4kg were recorded during the 2007/08 excavation relating to the early stages of the mound construction and from the summit. Three blocks were substantial, weighing between 30kg and 85kg, recovered from the upper organic mound. Dr. Joshua Pollard, writing for English Heritage, states: ‘It is clear from both the whole and fragmentary sarsens from the 2007/08 and earlier excavations that whole and fragmentary sarsens were deliberately incorporated into the makeup of the hill’. He later adds: ‘The early stages of mound construction were also intimately associated with sarsen’. Mr Pollard also observes: ‘Merewether (in 1851) records related ‘depositional acts from the primary mound, where bone fragments (including large mammal ribs), small sticks and an antler tine had been placed on top of several of the stones. This explicit depositional link between sarsen and organic materials stands in stark contrast to the seemingly deliberate exclusion of bone and antler from the stone hole fills of contemporary megalithic settings in the region’

One of the principle models used by English Heritage to radiocarbon date the construction dates at Silbury hill suggests a 95% probability of the following:

– Lower organic mound constructed 2460-2375BC

– Upper organic mound constructed 2460-2370BC

– Bank and Ditches constructed 2435-2330 BC

– Final Mound constructed 2450-2375 BC (52%) or 2355-2295 BC (43%)

Plant remains from the mound include dandelion, buttercup, stinging nettle, hazel, elder, thistle, sedge, wheat, barley, cereal, dock, willow, watercress, cabbage, brambles, sloe, crab apple, hawthorn, rose family, clover, forget-me-not, hemp nettle, ground ivy, meadow grass and a number of other grasses. Pollen counts from analysed samples include Scots pine, yew, elm, oak, birch, alder, hazel, lime, willow and ash. Animal bones relating to cattle, red deer, sheep, goat, badgers and moles were identified.

The poem in the Urn

Suggested by the opening

made in Silbury Hill,

Aug 3rd 1849

Bones of our wild forefathers, O forgive,

If now we pierce the chambers of your rest,

And open your dark pillows to the eye

Of the irreverent Day! Hark, as we move,

Runs no stern whisper through the narrow vault?

Flickers no shape across our torch-light pale,

With backward beckoning arm? No, all is still.

O that it were not! O that sound or sign,

Vision, or legend, or the eagle glance

Of science, could call back thy history lost,

Green Pyramid of the plains, from far-ebbed Time!

O that the winds which kiss thy flowery turf

Could utter how they first beheld thee rise;

When in his toil the zealous Savage paused,

Drew deep his chest, pushed back his yellow hair,

And scanned the growing hill with reverent gaze, –

Or haply, how they gave their fitful pipe

To join the chant prolonged o’er warriors cold. –

Or how the Druid’s mystic robe they swelled;

Or from thy blackened brow on wailing wing

The solemn sacrificial ashes bore,

To strew them where now smiles the yellow corn,

Or where the peasant treads the Churchward path.

Emmeline Fisher (1825-1864)

More on Emmeline Fisher here. and here.

Pete Glastonbury spent some time inside Silbury Hill during the excavations of 2007/2008 and has kindly allowed Silent Earth to share a small selection of his unique photographs during the visit below.

Thank you to English Heritage for the information here, largely sourced from its 2013 publication Silbury Hill: The Largest Prehistoric Mound in Europe and the contributors quoted in this article.

Thank you Pete Glastonbury for use of the photographs inside Silbury hill and Brian Edwards for the link to his 2010 article published in Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine ‘Silbury Hill Edward Drax and the 1776 excavations’ here, ‘Stukeley’s bridle’ here. and A Missing Drawing and an Overlooked Text: Silbury Hill Archive Finds here.

Brian Edwards article published in Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine ‘Silbury Hill: Stukeley’s bridle and other finds , some reports from 1771 and 1850’ is here.

‘A Missing Drawing and an Overlooked Text: Silbury Hill Archive Finds’ an article by Brian Edwards published in Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine here.