Stonehenge, Avebury and Drombeg Stone Circles Deciphered – A Review

WRITTEN BY Austin Kinsley ON 26/11/16. Stonehenge, Avebury and Drombeg Stone Circles Deciphered – A Review POSTED IN General Stonehenge

A guest review of Dr. Terence Meaden‘s recently published book Stonehenge, Avebury and Drombeg Stone Circles Deciphered, by Simon Banton the archaeoastronomer.

Dr G. Terence Meaden, M.A., M.Sc. D.Phil., F.R.Met.S. is a professional physicist, meteorologist and archaeologist with undergraduate and doctoral degrees in physics from Oxford University and an MSc in archaeology from Oxford University. He has made significant contributions to research in solid state physics (1957-1972), tornado climatology (1972-2014) and Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeology (1981-2016), with over 200 papers and numerous books published.

The complex interplay of light and shadow at megalithic monuments is a mostly unremarked phenomenon.

For those people who gather at these sites on significant days of the year, the focus — and the direction of their gaze — tends to be towards the rising or setting sun.

Dr. Meaden is one of the few who have made a habit of turning their back to the sun and, instead, he has paid attention to where the shadows fall. As a result, he has perhaps hit upon a crucial aspect of the design of these monuments and thereby given us an insight into the thinking of the Neolithic mind.

Building on his previous work spanning over 40 years, and taking as a starting point the idea that standing stones fall into male and female types based upon their shapes, he suggests that the key to it all is a symbolic union of the god and goddess.

This hieros gamos, or sacred marriage, is represented by the shadow of male, pillar-shaped stones falling upon female, lozenge-shaped receptors at key times of the year — the solstices, pseudo-equinoxes and cross-quarter days.

Using the stone circle of Drombeg in County Cork, Eire, as his reference site, he shows clearly that interesting shadow-play effects occur on each of the eight significant dates in the solar calendar, and he manages in the process to explain exactly why certain stones are positioned in particular non-obvious places.

A major bone of contention in the archaeoastronomical world is whether the concept of an equinox could have had any meaning to ancient people.

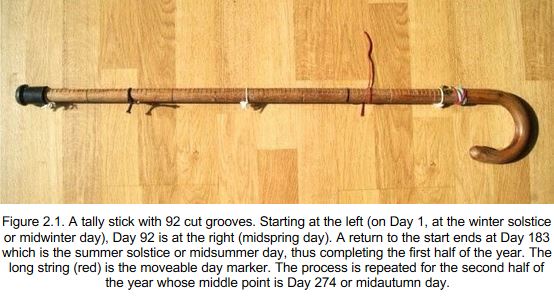

As they lacked any mechanical means of determining which days of the year had exactly 12 hours of light and of darkness, the belief is often expressed that supposed alignments on these days are the figments of our modern imagination.

Dr. Meaden elegantly torpedoes this by the simple expedient of a tally stick and a day counting method which neatly divides the year into eight. Importantly, the shadow-play that he identifies works correctly on the resulting pseudo-equinoxes.

Below: The tally stick that Dr. Meaden uses to illustrate a day counting method, reproduced from page 24 of his book.

With Drombeg fully described, he goes on to apply the concepts to Stonehenge and Avebury with notable success, taking in Knowth and Newgrange along the way.

This is a valuable addition to the body of literature that seeks to explain the reasoning behind megalithic sites, and, while some will undoubtedly find things to disagree with, the facts of the case are plain to see.

To shed new light on these monuments by means of shadows is no mean achievement.

Dr. Meaden contemplating the mysteries of Drombeg stone circle during the autumn equinox week in September 2016

An extract of chapter 2 ‘The reconstructed Neolithic and Bronze Age solar calendar with suggested agricultural festival dates’ is available to read here.