William Barnes, the self-taught Dorset writer and poet, concisely described folklore in his ‘fore-say’ to Dorsetshire Folk-lore by John Symonds Udal as: ‘Folklore, taken in broad meaning, is a body of home-taught lore, received by the younger folk from elder ones in common life, and in the forms of knowledge or faith, or mindskills and handskills’.

William Barnes, born at Bagber in the Blackmore Vale on 22 February 1801, hoped he had ‘done some little to preserve the speech of our forefathers’ and was a great advocate of a pure speech. For example, using the suffixes of ‘lore’ and stead’, ornithology becomes birdlore, pathology: painlore, geology: earthlore, astronomy: starlore, optics: lightlore, an aviary: a birdstead and a museum, a lorestead. None of these terms remain with us today, but the word ‘folklore’ has stubbornly persisted in our language through to modern times, as has the folklore of Dorset.

‘Her evil wish that had such pow’r,

That she did meake their milk an’ eäle turn zour,

An’ addle all the eggs their vowls did lay ;…

The dog got dead-alive an’ drowsy,

The cat vell zick and woulden mousy ;

An’ everytime the vo’k went up to bed,

They wer’ a hag-rod till they were half dead’

– A Witch by William Barnes

Below: A bronze statue of William Barnes at St Peter’s Church, Dorchester installed in February 1889, more here.

For generations Dorset has claimed a reputation as a rural backwater, its ways observed and recorded for perpetuity in the writings of William Barnes and Thomas Hardy, who each had a natural devotion to the county, being ‘Darzit bred’. Each in their own day lamented the inevitable passing of the old ways, which they observed with their own eyes in their own life times, that inexorable express train of modernisation, which continues apace to this day. Here in 2018, not a single mile of motorway runs through the rolling hills of our county, popular as a holiday destination for its Jurassic Coast, the Tolpuddle Martyrs, and perhaps also as a place where the old ways linger.

In October 1902, in correspondence with Thomas Hardy, Henry J. Moule, the first curator of the Dorset County Museum wrote:

‘Yesterday a hare could think of nothing better to do than to run all up South street, across Bull Stake and up Pease Lane (the Dorchester council, with doubtful wisdom, has obliterated these historic names). At the top of the lane, opposite Miss A’s stables someone killed it. People who saw it, or heard of it, said that this vagary was a sure sign that there would be a fire here within a week. So certain of this was a fireman that he said he was half inclined not to go to bed last night, as it was more than possible that he should be roused before morning by the fire bell. Well, it was not so prompt in fulfilment-this prophecy- as he feared. But it is a fact that this morning there was a fire, and, of all places at Miss A’s stable. Soon put out it was, I believe; but some of our friends in the bottom of their hearts have, very likely, a thought that the ghost of the hare had to do with it’.

George Ewart Evans and David Thomson write in their 1974 book The Leaping Hare:

‘A widespread country superstition in Britain: if a hare runs through a village street a fire will break out in one of the houses very shortly afterwards. This is only a feint echo of the deep-toned myth linking the hare with sacrifice’.

The Names of the Hare, with a translation from the Middle English by Seamus Heaney, is here.

In 1935, Marianne R. Dacombe published ‘Dorset Up Along and Down Along’, a collection of history, tradition, folklore, flower names, and herbal lore, including contributions collected via the Dorset Federation of Women’s Institutes. It recounts the following story from the Dorset village of Marnhull in the Blackmore Vale:

‘Jimmy Coombs with his wife, Fanny lived in a tumble-down cottage at Marnhull Common. When the hare coursers wanted to start a hare, Jimmy could always find one for them for payment of half a crown. After a short race, the hare always doubled back to Jimmy’s cottage and was there lost sight of. One day a scout was posted in ambush at the cottage to await the hare’s return. It ran right into the cottage and immediately turned itself into a woman (Jimmy’s wife Fanny). Her face was scratched and bleeding and her hair disordered and torn.’

The late Mrs. Fudge of Marnhull told the following story:

‘As I was standing at my door, (a cottage at the foot of Church Hill) I saw a woman coming down the hill who was a witch or a hag. She saw me laugh at her. After I went to bed that night I felt a weight on my legs which gradually went upwards to my chest. I screamed and my son came in the room. As he opened the door, the lump fell off, and I distinctly heard the hag walk down the stairs and out of the door.’ (In connection with the above the Marnhill contributor suggests that it is interesting to compare the article in the Somerset Year Book for 1930 p41 ‘When people have the nightmare in that part of the country a common remark is that they have been ‘hag ridden’; they actually believe that a hag comes to them during sleep and sits on their chest, causing the miserable symptoms of nightmare’.)

The turf Mizmaze at Leigh is mentioned in the above publication. Unfortunately, the maze was largely destroyed around 1800.

‘The most memorable spot near the village of Leigh is called the Miz-Maze. It is on high ground in an open field, and presents the appearance of a slightly raised flat mound, some places in diameter. In days too remote for our oldest inhabitants to recall, it was the meeting place of the holiday-makers of Leigh. As late as the year 1800 the maze existed, in the form of banks made to follow an intricate form. It is a pity that hardly a trace of all this now remains, as the situation is delightful as well as romantic. In the old days when the practice of witchcraft was fairly general, this spot was a noted gathering place of witches, and as it was remote from a high road or any big town or village, it was not an ill chosen locality for the purpose. Tradition has it that the last witch who was burned in England was arrested when attending a conference in the Miz-Maze here at Leigh.’

Kartherine Barker in her article The Mizmaze at Leigh, in reference to Leigh Common, adds:

‘Running behind the village houses on the south (top) side is a row of narrow fields, or tofts, separated from the common by a long and continuous hedgerow, most of which is still in existence. At the eastern (left) end of the hedge where it joins the stream is Hitchens Corner. It is a name which has persisted; in 1840 several closes in the area all carry the name Hitchens and today is Hedgings or Hedgins. ”Many years ago” wrote Barnes in 1879, ”I was told by a man of this neighborhood that corner of Leigh Common was called Witches’ Corner.” Barnes later came across some old depositions from Somerset magistrates of the years between 1650 and 1664, which recorded a Witches’ sisterhood that sometimes met on Leigh Common. Barnes saw Witches’ Corner as a folk memory of their meetings.’

There was also a turf maze at Pimperne in Dorset, said to have been destroyed by the plough in 1730. John Aubrey, after whom the Aubrey holes at Stonehenge are named, was educated at nearby Blandford school, of which he wrote in his diary in the 17th century (as interpreted by Ruth Scurr in her highly readable book John Aubrey, My Own Life), ‘I have found as much roguery at Blandford school as there is said to be at Newgate prison’. He also wrote in his diary that year, ‘Sometimes, on holy days or play days, we boys go to tread the maze at Pimperne, which is near Blandford.’

Dorset County Museum have written of the turf mazes at Leigh and Pimperne in Dorset here.

Below is a photograph of the Mizmaze in the neighbouring county to the east of Hampshire, this well-preserved labyrinth is at Breamore. According to tradition, nearby monks engaged in penances here, traversing it on their knees, with prayers said at certain points along the path. These sites are difficult to date and their origins are not known.

More on the Breamore Mizmaze here and other turf labyrinths can be found here.

Below is a photograph taken of my father in the late spring of 2017, visiting the Dorset village of Dewlish where he lived as a child for a number of years in the 1950s with his mother, stepfather and seven brothers and sisters. He was employed as a farm labourer for some time by the Voss family. This is the farmhouse at which, after the harvest was in, Mrs. Voss would prepare a celebratory meal for all the farm workers, including him. I have recounted certain of his memories of those far-off days in an earlier blog post here. There is an oft-repeated and tragic story as to why the window to the upper right in the farmhouse (seen here) remains bricked up to this day, which is told here. I was not originally planning to mention this well-known and achingly sad story in this article, but Auntie Sylvia recalls ‘When we went past at night, coming home from Sandbanks, we were frightened that we might see Betsy Caine riding on an old wooden hurdle near there, as that’s the story we were told — that she still haunts there, and as kids we thought that was true.’

‘So drink, boys drink!

And see you do not spill :-

For if you do

You shall drink two ;

‘Tis by your master’s will’.

Other recollections from ‘Dorset Up Along and Down Along’:

‘My informant is a native of Pimperne, and her relatives have been associated with the village for many years. Supposedly several members of the family have been overtaken by the ghost. It is thought to be a dog, which dashes along the Salisbury road from the foot of Letton Hill towards Pimperne, with much rattling of chains. When brave folks have stretched out a hand to grasp the chains of the ghostly animal, all they’ve felt was the brush of a soft velvety coat against the hand as the totally invisible creature careered madly on its way’.

‘Old Blandfordians have seen the ghostly sheep which runs from Gas Works Corner into the old burial ground in Damory Street’.

‘At Horton a black dog is reported to run across Pot Lane, but no one now owns up to seeing it’.

‘At Shipton Gorge a man walking home late one night met a black dog. He threw a stick at it, and the stick passed right through the body of the animal. The dog disappeared without a sound, politely leaving the stick where it fell’.

‘An inhabitant of Wimborne remembers being told as a child of a great hole in the ground on the hill going up to Rowlands, where at 12 o’clock at night might sometimes be seen to appear horses without heads driven by drivers without heads’.

‘At Marnhull a funeral was supposed to be seen at midnight (on a certain date) crossing Sackmore Lane from Fillymead to Dunford’s. There were no mourners following and the faces of the bearers were hidden beneath the pall which covered the coffin. According to local belief, it went along the line of the fighting. (N.B.- This refers to the supposed battlefields near Todber, near to the quarry where so many human remains were found in 1870). The same funeral story is told of Grove Field near Nash Court, which is practically in a line from Fillymead to Todber. A local explanation of the name Todber is ‘Trod Bare’ ie, by the troops at the time of the fighting’.

‘On the edge of the wood just opposite the knoll at Corfe Mullen stands Soldier’s Clump. Tradition has it that many soldiers lie buried there. When they fell no one knows, but they say it was from fighting in the direction of Badbury Rings and there is an old pollard oak nearby said to be full of bullets! Old Kitty would never go there gathering sticks after dark for fear of meeting the soldiers who walked there’.

Below: Badbury Rings Iron Age hill fort, where ‘yesterdays’ palpably linger in the atmosphere of the site, which is steeped in legends and tales.

‘At Shipton one day, while a chimney sweep was engaged at work, he brought from a chimney a bullock’s heart, stuffed with pins, the strangest thing being not that a heart should ever get up a chimney at all, but that the pins were all stuck in the wrong way, that is, they were pointing outward, like the prickles of a hedgehog’.

‘In 1930 alterations were being made to Dale House in Salisbury Street Blandford, in the course of which an old and solid partition wall was demolished. Built into the wall was discovered an ancient, crumbling broom, a survival of the days when it was believed that a besom so placed would bring luck to the inhabitants of the house. This broom was replaced’.

‘Wart cures are numerous. At Corscombe and Halstock, you are told to steal a bit of raw beef and touch every wart with it, then bury the meat, not telling anybody where it is, and as the meat rots away the warts will disappear’.

‘The Dorchester contributor has heard of a highly useful spell which will blister and burn your enemies — just throw a handful of salt on the fire in the morning, that is all!’.

At Cheselbourne a certain man, Tom Trask, had the misfortune that whenever he slept, the devil threw the ceiling down on his head’.

‘On the hills above Marshwood there are three clumps of trees called the ‘Devil’s Three Jumps’; the legend is that on certain nights of the year the Devil was seen jumping from tree to tree’.

John Symonds Udal’s Dorsetshire Folk-lore, to which William Barnes contributed, reaches back to the 1870s and was published in 1922. A brief selection of the stores of folkore and custom he studiously gathered over many years into a book is included below:

A ‘writer in the Somerset and Dorset Notes and Queries (1911), vol xii p. 232, states that an old Dorset woman, aged about 86, told him that she had been taught by her grandmother never to throw away soapy water on Good Friday. An editorial footnote confirmed the existence of this belief and added that it was also said that soapy water thrown away at this time turns to blood’.

‘Another Dorset writer, Mr. Wilkinson Sherren, in his Wessex of Romance (1908), p. 17, mentions the fact that in Moreton Church sprigs of English willow and pieces of yew tree are placed at the end of every seat on Palm Sunday and Good Friday, and that no one in the village remembers when this custom was not observed’.

Miss M.G.A. Summers of Hazelbury Bryan, in the Folklore column of the Dorset County Chronicle in 1881, observed, ‘If you sit in the church porch on Midsummer Eve you will see those who are to die during the ensuing year enter the church and not come out again; whilst those who will have a serious illness will go in and return again’.

William Barnes gives a matrimonial oracle, ‘which consists of a girl going to bed on Midsummer Eve, putting her shoes at right angles to each other in the shape of a T, and saying :-

Hoping this night my true love to see,

I place my shoes in the form of a T’.

Rev. W.K. Kendall recorded ‘A very curious form which the customary bonfire celebration on the Isle of Portland on the night of 5 November had taken. When the bonfire was lighted, the following custom was observed. A man taking up one of the children in his arms gave the signal, and then all the others followed him in single file round the fire, over which he leaped with the child in his arms. When the fire began to burn low, the children also jumped over it. The following doggerel was sung:-

Wood and straw do burn likewise.

Take care the blankers don’t dout your eyes’.

In 1872 John Udal makes first mention in Notes and Queries of the skull of Bettiscombe Manor. Dorset County Museum have written a comprehensive article on the legend of the skull here.

‘The late Mr Charles Warne, FSA in his Celtic Tumuli of Dorset (1866) states that on Bincombe Down there is a ‘Music Barrow’ of which the rustics say that if the ear be laid close to the apex at midday, the sweetest melody will be heard within’.

‘Dr. Maton’s Observations on the Western Counties of the Cerne Abbas giant writes, ‘There is a tradition among the vulgar that this was to celebrate the destruction of a giant, who, having feasted on some sheep at Blackmore and laid himself down to sleep after his meal on this hill, was bound and killed by the enraged peasants on the spot’.

Below: The Cerne Abbas giant. To the upper right of the giant’s head can be seen a small rectangularish banked and ditched enclosure, known as the Trendle or Frying Pan. John Udall writes that the villagers of Cerne during the annual May day festival of the Maypole set up the pole here ‘not on the village green as was usually the case’.

Below: A Medieval wall painting in St Mary’s Church Cerne Abbas, described by the church as ‘just above the altar rail is a circle containing a six pointed star which is said to be one of the consecration marks, usually crosses of the original church’. Similar apotropaic markings in old buildings have been described as charms against witchcraft and evil spirits, more here.

More on the Cerne Abbas giant here.

‘With the rose and the lily

And the daffodowndilly,

The lads and the lasses a-sheep-shearing go’.

From Thomas Hardy’s Under The Greenwood Tree, more here

.

Below: Corfe Castle, gateway to the Isle of Purbeck and occupying an imposing defensive position. The base of this steep sided chalk hill is nearly surrounded by two small brooks, the Wicken and the Byle, which meet here and flow as one stream into Poole Harbour. The ruined castle stands defiantly against all that history has thrown its way: the murder of a Saxon boy king in March 978AD; a siege throughout the gloomy winter of 1644-45 during the English Civil War; its ultimate surrender on 27 February 1646; and, on 5 March 1646, the final nail in the castle’s coffin — a formal vote in the House of Commons to demolish it. A summary of the history of the castle is here.

Below: Maiden Castle Iron Age hill fort to the west of Dorchester. In Dorchester Antiquities, published by H.J. Moule in 1906, he writes ‘it may be noted, but without the slightest hint of opinion, that there is an old tradition of an underground passage from Dorchester to Maiden castle’. More on Maiden Castle here.

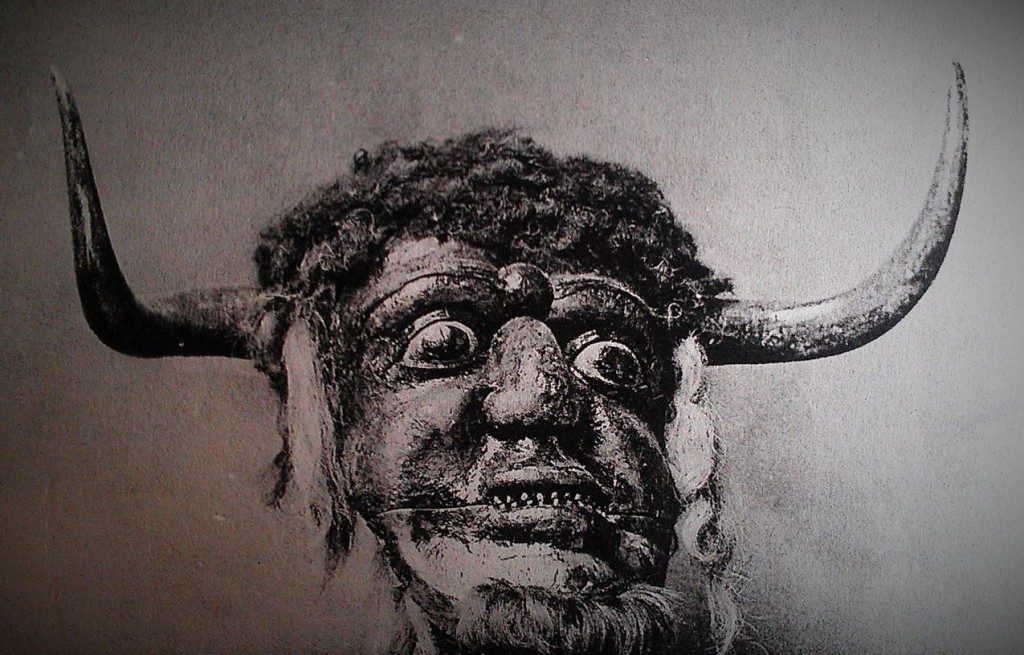

The most iconic object of the old traditions, legends, rituals, and folklore of Dorset is the Dorset Ooser, formerly in the possession of Mr Cave of Holt Farm, Melbury Osmond. An article on the horned mask by Dorset County Museum is here. It is said to have disappeared around 1897 under mysterious circumstances.

Below: One of only two known photographs of the original Ooser, taken between 1883 and 1891 by J.W. Chaffins and Sons of Yeovil. More here.